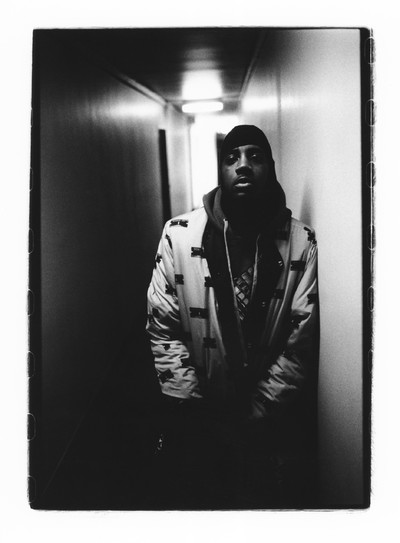

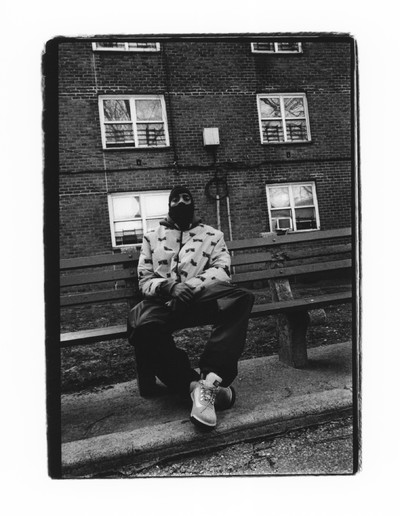

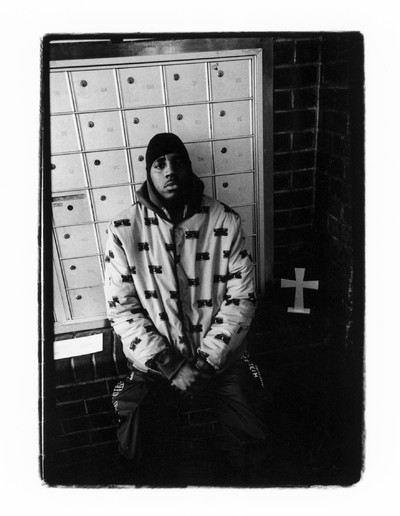

Hood Spirituality

Photography by Christopher Currence

Hood Spirituality

Photography by Christopher Currence

In his experiments across sculpture, drawing, and filmmaking, Ron Baker explores the tension between the hyper-local and broad historical influences that shape contemporary consciousness. Incorporating objects of spiritual significance as well as daily functionality, he builds works that are active, releasing past wrongs or offering invocations for the future. Baker founded the Bronx collective, Public Housing Skate Team, and allows his practice to flow between gallery shows, streetwear design, and community-based projects.

Your work is pretty supernatural. Even surreal. There’s this mix of African masks next to coke bags, guns. You told me you call it “hood spirituality.” What do you mean by that?

I love that—and I think it describes a very real subculture that often gets ignored. You get it in certain movies, like “

Exactly. I relate to that. Parts of that mishmash may feel stagnant, but it all comes together and moves together.

Moves together and also moves across people, which I find to be the craziest thing. Looking at your work and then work from someone in London or Paris, there’s this real sense of thinking through the same ideas at the moment. It’s almost an expression of a collective subconscious.

We’re all under one hard drive, that’s for sure. Sometimes you have an idea and you see someone else doing it too—it’s not necessarily like “Yo, you copied me,” though. Because

“Hood spirituality” is basically the concept of finding knowledge of self from a spiritual perspective, but also having an urban upbringing, growing up in the hood.

“Hood spirituality” is basically the concept of finding knowledge of self from a spiritual perspective, but also having an urban upbringing, growing up in the hood.

And maybe when a movement comes along, it’s just a particular thing that’s popping up under this one hard drive in these different places. It’s not a matter of copying, more that there are ideas and feelings that come around.

We all catch the spirit, you know. We’re really spiritual in the hood without even thinking about it, often. For example, someone passed in the projects where I live and these high school kids set up an altar in front of the building. They probably don’t even view it as an altar or realize how that goes back to African traditions, to worshiping a deity like Orisha or the ancestors). But on this altar in the hood, you see candles, pictures, etcetera, and then you’ll see the kids come after school and hang out around it. Like they’re hanging out with the spirit of the person. But they’re not viewing it that way, per se. It’s a social gathering for them.

It’s natural, not a conscious form of worship. Interesting. I guess that’s what you, as an artist, are able to see in these small acts—how they relate to a larger spirituality we share.

It’s shared but it’s also deeply personal. Like when you see people pouring Hennessy for a dead homie, which comes from Africa too. They might not know that, but it does.

It’s almost a spiritual memory that makes these things kind of automatic. It’s been 100 or 200 years since the practice started, and now people just do it. Some of the similarities in Black cultures from Sudan to West Coast, LA just blow me away. To see that connection.

We’re all energetically connected. That’s my guess. I don’t know if there’s a science behind it. I don’t know how you can measure it per se—

But maybe that’s a problem with our contemporary way of thinking—that everything has to be measured. The ancient Egyptians used to believe in 360 senses. 360 senses, man!

[laughs] Yeah, and we only talk about five now.

We’re so rooted in the material world. Everything’s scientific and reductive—that’s why I’m interested in this desire for spirituality amongst us. That’s what art can be. It can be a vessel to try to get you to question things beyond the material world.

When I started making art, one of the main questions that hit me was wondering what my ancestors were practicing before the colonizers came.

When I started making art, one of the main questions that hit me was wondering what my ancestors were practicing before the colonizers came.

Anywhere else that you go to often for inspiration?

We had a crazy one in Paris, which burnt down. They were selling everything—you could ask for anything from a Torah to a voodoo doll. Actually, my friend just had a crazy situation. He was given a mask from Benin recently—and Benin is known across the Arab and African world as a country that practices a lot of black magic. Anyway, he put this mask up in his house, but he was shaken up about it. It had a weird energy. So he decided to throw it into the river, to get rid of it in a ritualistic way. And I was like, “That is not a good idea.” I told him to just leave it alone. But he went and did it anyway. And later that night when he got home he felt this really dark presence. Then the glass started shattering in his room, his iPhone stopped working, everything went wrong. He had to call a shaman, and apparently when the shaman came into the room he started throwing up because of how strong the presence was from this fucking mask.

Damn. Yeah. It’s deep, that kind of magic.

I grew up around so many stories like that, about the unseen. That’s what I was getting at with the ancient Egyptians—these things were not theories. They knew it as a fact. It was a very real form of knowledge. But now, we’ve limited human experience. We don’t even understand what we are.

We’re way more powerful than we think.

We are way more powerful than what we see on the surface. We only use our five senses, we only see a certain percentage of reality, but we’re capable of so much more.

We are way more powerful than what we see on the surface. We only use our five senses, we only see a certain percentage of reality, but we’re capable of so much more.

I feel your work is about that search for what we’re capable of, about finding something beyond physical reality in the most unexpected places.

It’s true. I’m really into these statues from the

I love that book—it’s pure negative to positive. I mean they called him Satan in prison—

Yeah, he goes from robbing and stealing and dealing to raising his vibration, trying to help make change. Trying to help teach our people about who we really are: kings and queens. So I got really into seeing how people fought back, mixing that with some hood elements, with some other Black American traditions like Voodoo practices in Louisiana, or Santeria.

Some of that is very serious stuff. Do you ever get scared?

No, I don’t get scared because I know my intent.

Your intent is knowledge.

Knowledge and learning—knowledge about the art, about our shared history, and also knowledge of self. Fear of all of that comes from the oppressor. They made us scared of our own traditions, our own religions. So I don’t get scared. It’s part of this forever-search. When you’re on that path of knowledge with good intentions, the right answers start to come along. If you really want to find the truth.

If Dubois posed a “double-consciousness,” defining it as the strange sense of two-ness, the split-self of the black person displaced in another land becoming “two souls, two thoughts, two un-reconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body,” then, now, it is appropriate to suggest that double has multiplied. We live in a time where there’s cause for the advent of a triple, or quadruple, or perhaps best put, a multi-consciousness. The diasporic black experience is uniquely marked by a permeating sense of dichotomy, between the sense of blackness and the opposing realities and ideals of the society the black person is displaced in. What is of vital interest is the additional layers of consciousness that have arrived with the passage of time, for the children of the second, third or fourth generation, of whom there isn’t the imminent displacement from one to another, only the idea of another place, or the teachings and passings on through previous generations of ideals, myths, religion, and sensibilities. It is strange enough, that one is taught and raised in the African common belief of the unseen, and then lives in a secular West. But, the contemporary phenomenon of multi-consciousness isn’t limited to race or diasporic displacement alone, it is shared by most – we live between multiple realities: the Internet, the television, day-to-day life, the realities of the various ideologies and religions of the present era. Layers of reality that topple over one another, producing a mass state of confusion, and a subsequent search to remedy it. But, the black person, now, perhaps lies at the base of the flame, in an exaggerated chasm, facing the conflicting realities of the contemporary world, and dragging on in a perpetual state of non-belonging that ultimately produces this new, unique form of existence – a surreal existence, which in turn, has led to, in the case of a few chosen artists that represent this new sub-movement in art, a body of work that I want to call New Black Surrealism.