Underwater

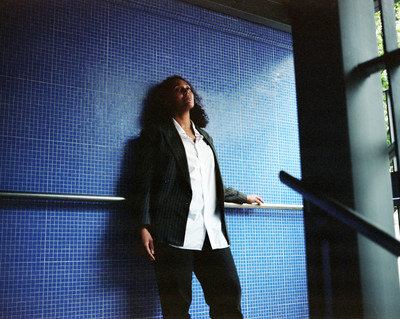

Photography by Michella Bredahl

Underwater

Photography by Michella Bredahl

Dominique White sculpts large-scale work and produces installation pieces in response to the idea of hydrarchy—the ability to gain power through the instrument of water. Drawing on her research into the slave trade and extensive knowledge of critical theory, White traces the relationship between the ocean and Black subjectivities. She defines her work as revolving around the notion of the “Shipwreck(ed): a reflexive verb and a state of being.” Materials are put under stress in White’s pieces, with destroyed sails, anchors, and buoys uniformly coated in white-clay and then precariously suspended—taking up questions of industrial function and natural resistance, the oppressive force of the State and the freedom of the soul. White is currently working on “Deadweight,” a ship that she will build, sink, and dredge up, for exhibitions in Italy and London as part of the Max Mara art prize.

So you grew up in Essex, right?

Yeah. I spent time in the Caribbean growing up too—my mum’s half Saint Lucian and my dad’s Jamaican. So I definitely feel I’ve been spread across many places. But I haven’t been back to the Caribbean for close to fifteen years now—really because of family drama. I have a very dramatic family. So, I’m taking some distance from that.

Did you feel that moving between those places had an influence on you—on your personal life, but also on your work?

I completely understand that. Do you feel that, in a way, your work is where you try to come to terms with that sense of impossibility and access it?

Probably not access. For me, impossibility is a combination of

It’s funny, I never considered it that way before. I’ve heard you speak about Afrofuturism as it compares to your work, but I always thought it was about trying to find a reality beyond the stories and myths we grew up with. What you’re saying now is a step further removed: we’re trapped in this very real present of late capitalism and any future reality is an impossible imaginary.

It’s not necessarily about being trapped, exactly. It’s more this knowledge that even if we were successful in escaping our current reality, it would chase us. I was introduced to Afrofuturism through listening to

Right—it’s more that those ideas were possible when there was still something unknown, but now, we know.

We’re actually discovering all of the unknowns, yes. What were once considered really ‘out there’ ideas of escape have very quickly been brought back to reality. The only way of escaping this reality is by doing the impossible, which is destroying it. I just read this book by

I mean I’ll read it and then we’ll talk about it. But from what I can gather, there’s this idea that I gain freedom in a certain way, but I’m still in life. I can’t escape life. And that’s where nihilism comes in.

That’s what I’m saying. If you continue to ask for your rights, they may be given to you. But that means someone else is giving them. There’s this need to escape that reality. But what you’re raising in the broader picture is that, even if we do get out, where do we go exactly? Even if we fix the world, or we find something close to Utopia, isn’t the nature of the world inherently dystopian? We’ll always just go back to our basic instinct to kill everything.

Given the current structure we live under, yes, but I don’t think the world has always been like that. I think it’s a modern phenomenon from the past 400 or so years. The best analogy I’ve found for today’s society is the slave ship: we’re being held below deck and we know that even jumping overboard or being thrown overboard is futile, we’ll just be recaptured. So, in order to prevent being recaptured, we have to destroy the system. We have to destroy the ship itself. I actually just read

If you can’t escape, if surveillance in society or on the ship is everywhere and there’s no way of becoming invisible, you have to destroy it from within. And if we don’t destroy the entire thing, we’ll continue living in a cycle. I guess I don’t really believe in societal reform!

If you can’t escape, if surveillance in society or on the ship is everywhere and there’s no way of becoming invisible, you have to destroy it from within. And if we don’t destroy the entire thing, we’ll continue living in a cycle. I guess I don’t really believe in societal reform!

Oh, I don’t believe in it at all. If a car is broken, there are only so many times you can try and fix the parts—eventually, you’re going to have to buy a new car.

But the thing is, society isn’t broken. It’s functioning as it’s designed. It’s working as it was designed to work since day one—which means, of course, that it doesn’t work for people like us. I guess that’s why I’m enchanted by this idea of the impossible and this idea of complete destruction. It’s why I’m more of a nihilist than a pessimist.

I love that the ship analogy is made very concrete in your work—it’s been a recurring form that you use. On a massive scale, too. One that’s almost impossible to wrap your head around if you just see photos of the work.

And does the material eventually crash?

It will, with time. The idea is that I let the work retain autonomy. All the iron is untreated, so the atmosphere will eat away at it and, one day, in decades or centuries, it will collapse. The white material in my work is water soluble, so any moisture that’s introduced to it essentially melts it away. I have this romantic idea that the work should return to the sea one day, because then everything except the iron would disappear.

That’s extremely romantic. I love the fact that you leave the work to its own devices. Historically art has tried to conquer nature, but you’re not doing that.

A medium, exactly. As opposed to a creator or a conqueror, even. I remember seeing the classical statues as a kid,

All of the materials are purposely destroyed up to a certain point and then re-configured. It becomes a battle between the materials from there. I made this one piece and you could actually hear the work ripping in the studio because the tension was so high—when I heard that, I stopped and thought: “Well, that’s the work then. I can’t control it and it’s just going to keep ripping itself apart. It has to remain like that.” It’s why I don’t have a studio assistant actually, because whenever I start working with someone, they see my process they think I’m fucking insane. But that’s how I create tension between the fragility and the weight—so that the viewer feels they have no power over these objects. Sometimes because of the weight and balance, if it’s hanging, it’s almost as if it’s breathing—it starts to slowly spin in space. They’re very bodily, in a way. It’s why I really enjoy being a sculptor: being a mediator as opposed to a creator.

Which also makes me think of the role of conductor, or even DJ. It’s about sculpting with existing sound, mediating that experience. You mentioned

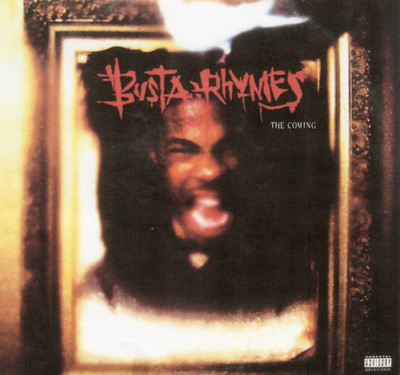

I’ve always gravitated to music, it’s very rare to see me without headphones on. Traveling, walking down the street, in the studio, there’s always music playing. I can shut off part of my brain that way and allow the work and music to flow together—I have specific playlists that I listen to in the studio when I’m producing, for example. It also helps give me access to a lot of heavy theory that I read, freeing me up to respond to it in a less intellectual, more physical way. I listen to a lot of Detroit techno, a lot of jazz, a lot of hip-hop, everything from pre-2001 Busta Rhymes to Drake and Rihanna, to Underground Resistance and Little Simz. It’s kind of all over the place, but I feel they’re all telling stories that feed into my work. I remember I was listening to Busta Rhymes having just discovered Black accelerationism and I was like

The connections between those mediums is so fascinating—because all of this work comes from the subconscious, from that strange mixture. It all blends together. Like Busta Rhymes and accelerationism, it all comes together.

If Dubois posed a “double-consciousness,” defining it as the strange sense of two-ness, the split-self of the black person displaced in another land becoming “two souls, two thoughts, two un-reconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body,” then, now, it is appropriate to suggest that double has multiplied. We live in a time where there’s cause for the advent of a triple, or quadruple, or perhaps best put, a multi-consciousness. The diasporic black experience is uniquely marked by a permeating sense of dichotomy, between the sense of blackness and the opposing realities and ideals of the society the black person is displaced in. What is of vital interest is the additional layers of consciousness that have arrived with the passage of time, for the children of the second, third or fourth generation, of whom there isn’t the imminent displacement from one to another, only the idea of another place, or the teachings and passings on through previous generations of ideals, myths, religion, and sensibilities. It is strange enough, that one is taught and raised in the African common belief of the unseen, and then lives in a secular West. But, the contemporary phenomenon of multi-consciousness isn’t limited to race or diasporic displacement alone, it is shared by most – we live between multiple realities: the Internet, the television, day-to-day life, the realities of the various ideologies and religions of the present era. Layers of reality that topple over one another, producing a mass state of confusion, and a subsequent search to remedy it. But, the black person, now, perhaps lies at the base of the flame, in an exaggerated chasm, facing the conflicting realities of the contemporary world, and dragging on in a perpetual state of non-belonging that ultimately produces this new, unique form of existence – a surreal existence, which in turn, has led to, in the case of a few chosen artists that represent this new sub-movement in art, a body of work that I want to call New Black Surrealism.