Master of Sex

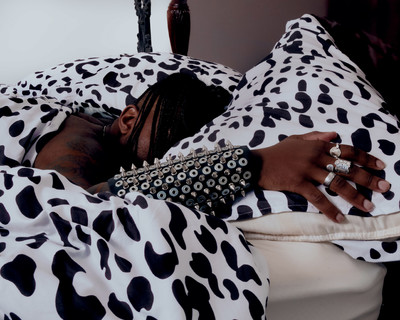

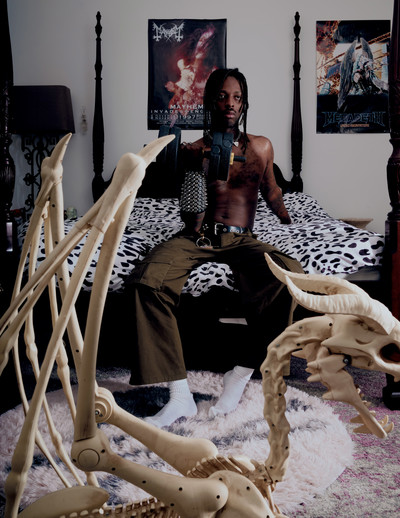

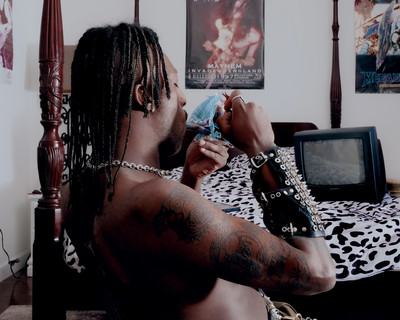

Photography by Michael Wolever

Master of Sex

Photography by Michael Wolever

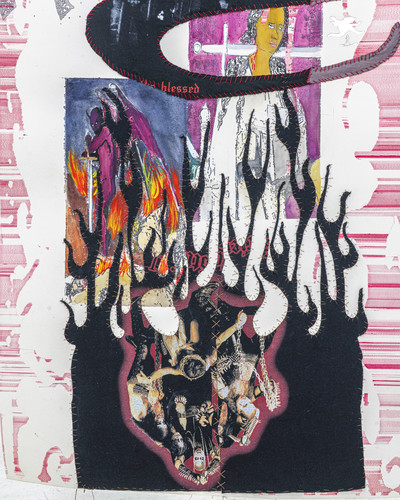

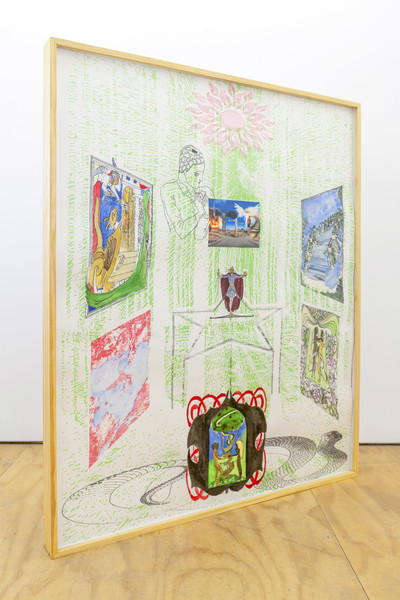

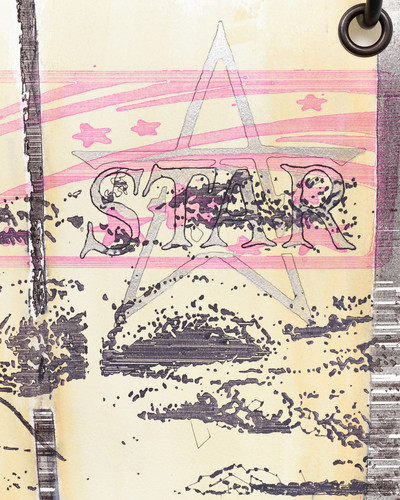

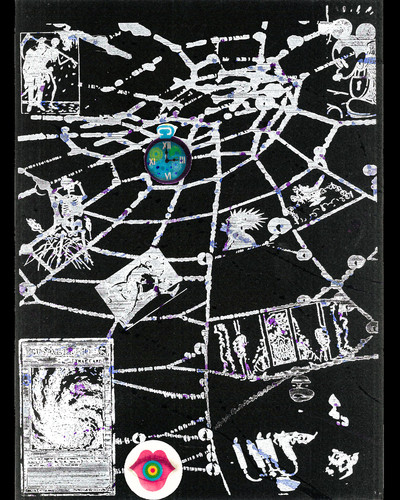

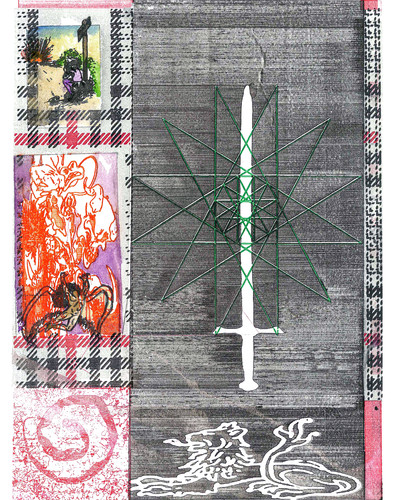

Chris Lloyd reimagines collage and scrapbooking as modes of self-expression, nostalgia, and personal myth-making in his multimedia works. Using a wide array of materials, from watercolor and embroidery, to found objects and laser engraving, Lloyd creates layered pieces that respond to moments in his history. Each piece is as multifaceted as Lloyd himself, referencing the religious imagery, death metal bands, and pop culture figures that have shaped his psyche, all while dealing with deeper questions of identity and the possibility of self-discovery through the act of making.

I’ve been thinking a lot about layers in your work—and how references accrue.

That’s what I think is central. It’s amazing because those references mean that my work expands as I expand, as I’m exposed to different things or go to new places. I’m building all these different worlds and I feel there’s more access than ever before. Even in terms of the different versions of self that are layered there, I feel way more comfortable owning those because I know now that when you put on this mask you’re presenting to the world—it may not be the most authentic version of you, but it is still a version of you.

Even if that image is what you want to make up about yourself, it still comes from your own consciousness.

So many of the conversations I’ve been having recently are about this—identifying your sources and references, and how being cognizant of that makes you a well-rounded person.

It makes the world a lot more interesting too. One of the nice things about the work you make is that it helps with a search for meaning, a search for knowledge. It’s work that aims to help.

Definitely, it’s a search. For example, my last show was called “I Against I,” which is a reference to a

Really? Wait, I haven’t heard about this.

It’s insane. The first skinheads were emulating Jamaican people that came to Britain in the 50s and 60s. All the young Jamaican kids would rock shaved heads and workwear. Other kids back in that day were mods, they were all wearing suits—but when they saw these Jamaicans they started looking up to them and dressing like them.

For this last show, I was painting fifteen minutes before the opening. It’s something that’s magical about my practice. It means I’m present and making decisions when I can see the whole body of work in front of me.

For this last show, I was painting fifteen minutes before the opening. It’s something that’s magical about my practice. It means I’m present and making decisions when I can see the whole body of work in front of me.

Jamaican style from London in the 60s and 70s is amazing. Tight leather trousers with boots, for example. People think it’s white style but it’s OG Black Jamaican style. That’s what I mean though—you have all these little references in your work that spin out into whole worlds. You’ve got biblical references, rock references,

I’m so glad that you picked up on that. What I’m trying to do is build something like a diary—like how, when you were a kid, you would scrapbook your favorite stickers, or notes, or whatever felt important to you. That’s what I’m aiming to evoke—and within that, each piece has its own specific purpose. “I Against I” was looking at patterns in my life—so I would take one pattern that I felt was self-defeating and then juxtapose it with its ideal version.

Parts of your personality versus how you’d like to be?

Right.

So there’s a very clear intentionality to the work. Do you feel, looking back, that pieces carry a certain emotional aura?

Definitely. When I look at old work, I can remind myself of what I was going through at that time. I can say “Damn, you overcame that. You worked through it.” Or sometimes it’s more like “You’re still dealing with that shit? Remember you were dealing with that last time!” My work is so affected by my emotions.

Do you make better work when you’re sad or happy?

Sad, I think.

Happiness is great and fleeting, but when you’re sad you brood over it.

It’s so true. For this last show, I was in London and I was technically done with all of it, but I couldn’t stop. I was painting fifteen minutes before the opening. It’s something I want to be better about, but I also feel it’s something that’s magical about my practice. It means I’m present and making decisions when I can see the whole body of work in front of me. I feel a closer connection that way than when it’s all planned out.

You create a structure that you can be impulsive within. It’s a framework.

I’m trying to give myself bounds and then explore within those. Sometimes my impulses take me so left field that I’ll have to destroy the piece, because it’s so far away from the rest. I definitely need to give myself a boundary.

Then again, with punk music, these motherfuckers don’t know how to play instruments. They just pick up a guitar and start hammering it out. That’s pure impulse, and it’s fresh and it’s amazing.

Yeah. Damn, I never realized how much I idolize impulse until this conversation.

We’re all driven by impulse—sometimes shared impulse. That’s why I want to talk about movements, and Black surrealism as this unfolding, international movement. There’s no focus in art history on Black movements—all the work gets lumped together, but there are impulses shaping a new generation right now, and that’s worth identifying.

I have a very Black metal and punk background, right? But

I want someone to see my work and already be able to imagine me.

I want someone to see my work and already be able to imagine me.

I’m really obsessed with the techno rave scene right now in Paris for exactly that reason. Stuff like Emma DJ—Pol Taburet is on his album “Godrime.” It feels so punk because it’s new, and fresh, and this crazy mix of rock, techno, rap, trap, etcetera. But what I really love is trip hop. Tricky, Massive Attack, Portishead. It’s all Bristol, which is so interesting because in English culture that’s where white and Black cultures really mixed together.

I feel that’s what I gained from traveling—it expanded my mind and gave me new points of reference. You see that in music—even UK drill versus New York drill. UK drill is still very drum and bass heavy, whereas New York drill is very trap—it’s cool seeing how people take the same style and make it their own based on their region or their references from growing up. I feel that’s exactly what I’m trying to do with my art.

That’s what I love. Especially, stylistically. I see you and you are what you represent. I love seeing all the different variations of how it comes out.

It’s beautiful to see how the same reference can affect so many different people. Back in the day, you had to be on the ground. If you were a punk, you were only a punk. You hung out at the punk spots and you knew about the punk shows because you were part of the scene. But now with Instagram, you can be a part of a scene without ever even being in the scene itself. It expands people’s realms.

Now, you don’t have to be a raver to wear raver pants. But we were wearing that shit so we could hide drugs in our pockets! It’s form versus function.

Now, you don’t have to be a raver to wear raver pants. But we were wearing that shit so we could hide drugs in our pockets! It’s form versus function.

It’s making the most insane shit, because it’s a huge mash up now. The only problem is that subcultures get wiped out so quickly.

Exactly, because it’s all about what’s “in.” Style used to come from your points of reference—what music you were into, what movies you were watching, what scene you were around.

What’s hilarious is all these little subculture styles that become mainstream so quickly. Like the whole Arcteryx thing.

And that was booster culture! People were going in there, racking as much Arcteryx as they could, and flipping it on the black market so they could make their bread. And now the people buying it from the boosters are trying to say it’s their original style. But they’re the licks! They paid $600 so someone could eat. But that’s the whole economy, which I’ve only just finally learned.

Exactly. I love fashion, but no one has style anymore—or anyone who does, it gets turned around so quickly into the mainstream and loses meaning.

Totally. Gatekeeping is lame, but sometimes it’s necessary. With my work, I’ll be digging through archives, sifting through all the bullshit, until I find the stuff that speaks to me. As much as I want to show people what excites me, I also worked really hard to find it. Sometimes that makes me hold back.

Especially when you feel you don’t have a place of belonging and you worked to make space for yourself. Then someone comes along and makes you feel you don’t belong there anymore, or worse, acts like you weren’t the one that made the place to begin with. It’s a weird new colonialism.

It is colonialism. Meanwhile we’re just searching for a sense of community through all our various art forms, be that writing, painting, or even DJing. We’re building this world where you can include people with the same mindset or sense of self as you. That’s what’s beautiful. That’s what we should aim for.

If Dubois posed a “double-consciousness,” defining it as the strange sense of two-ness, the split-self of the black person displaced in another land becoming “two souls, two thoughts, two un-reconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body,” then, now, it is appropriate to suggest that double has multiplied. We live in a time where there’s cause for the advent of a triple, or quadruple, or perhaps best put, a multi-consciousness. The diasporic black experience is uniquely marked by a permeating sense of dichotomy, between the sense of blackness and the opposing realities and ideals of the society the black person is displaced in. What is of vital interest is the additional layers of consciousness that have arrived with the passage of time, for the children of the second, third or fourth generation, of whom there isn’t the imminent displacement from one to another, only the idea of another place, or the teachings and passings on through previous generations of ideals, myths, religion, and sensibilities. It is strange enough, that one is taught and raised in the African common belief of the unseen, and then lives in a secular West. But, the contemporary phenomenon of multi-consciousness isn’t limited to race or diasporic displacement alone, it is shared by most – we live between multiple realities: the Internet, the television, day-to-day life, the realities of the various ideologies and religions of the present era. Layers of reality that topple over one another, producing a mass state of confusion, and a subsequent search to remedy it. But, the black person, now, perhaps lies at the base of the flame, in an exaggerated chasm, facing the conflicting realities of the contemporary world, and dragging on in a perpetual state of non-belonging that ultimately produces this new, unique form of existence – a surreal existence, which in turn, has led to, in the case of a few chosen artists that represent this new sub-movement in art, a body of work that I want to call New Black Surrealism.