Painting as Religion

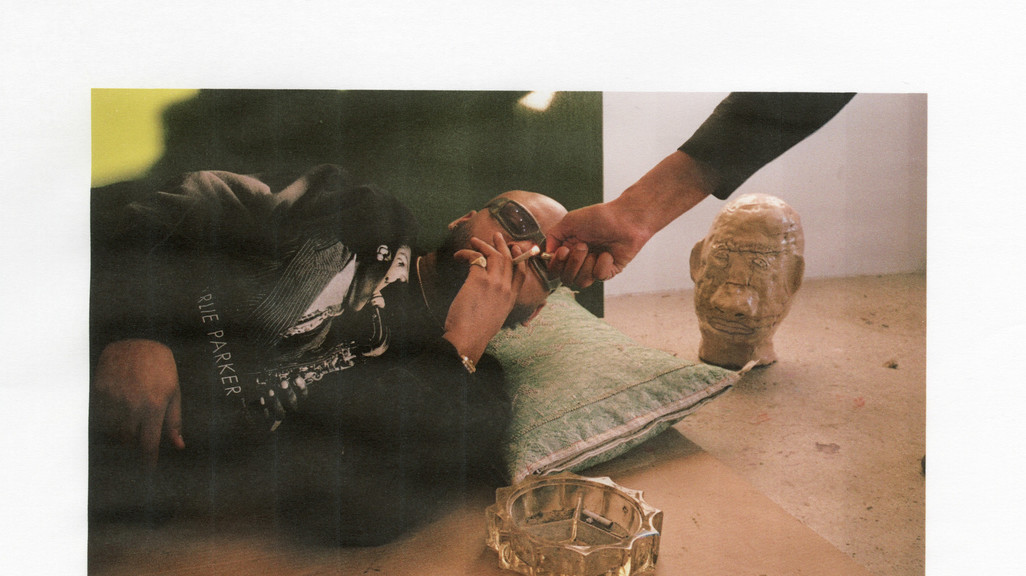

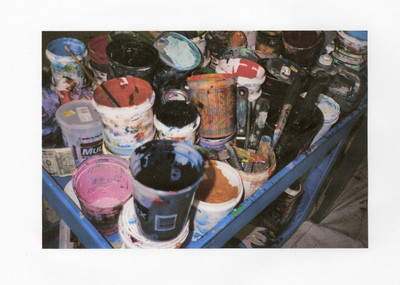

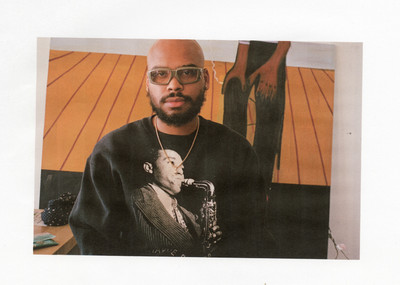

Photography by Adam Zhu

Painting as Religion

Photography by Adam Zhu

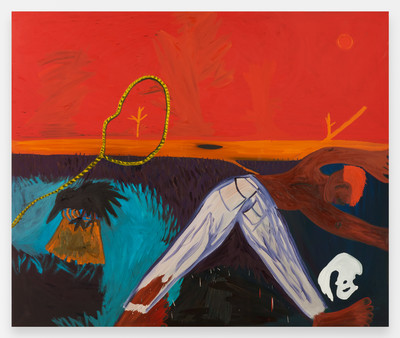

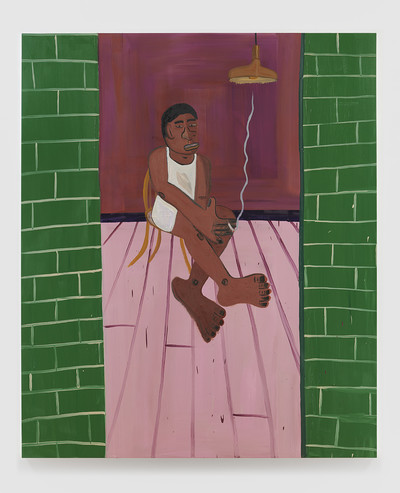

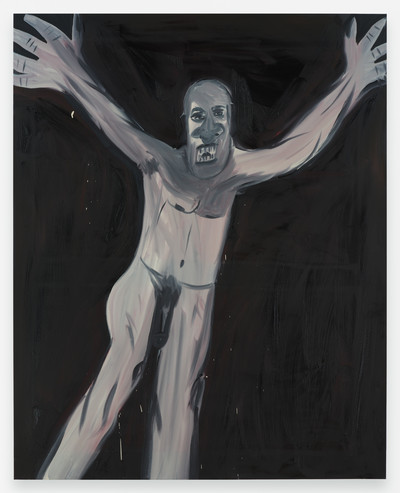

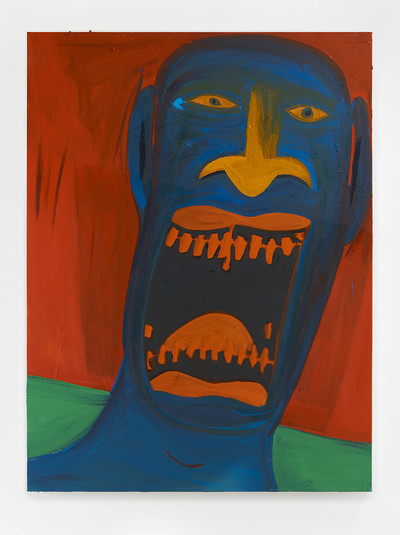

Marcus Jahmal’s canvases conjure what he calls “filtered realism”—just as figures and images from daily life transform themselves into meaningful metaphors in our dreams, so Jahmal’s personal memories and influences become haunting, symbolic scenes. Contradicting the traditional rules of color composition, Jahmal floats characters, body parts, and solitary objects above intensely-hued flattened backgrounds, creating the feeling of stage-sets—spaces in which every detail carries meaning. Twists on art historical references to the likes of Vuillard, Baselitz, Manet, and Picasso abound (Jahmal’s work was recently featured in the group show “Echoes of Picasso”), yet each piece remains grounded in the present. The result is the sense of a modern mythology unfolding in real-time.

I know you’re focusing on painting now, but when you first started out you were also working in music, fashion, lots of different fields, right?

Yes, even video games. But I felt I was going to spread myself too thin too early doing that. So I decided to just stick to painting. I credit my success to that decision—but after a while, you do get bored and want to start exploring other territories again. I’m feeling that right now.

There’s this strange pressure these days to only have one main career though—does that make you hesitate?

Definitely. People want to see you doing just one thing to believe that you’re serious. It’s a very New York social pressure, I’ve noticed. Everybody’s worth is based solely on this boiled-down career choice. When I meet people here, the first question is always “What do you do?” When I was younger, I felt I had to have a simple answer to that or I’d seem like a fucking jerk. But it’s a shit question and, in the end, seeing your self-value in that way will make you unhappy.

People want to see you doing just one thing to believe that you’re serious. The question is always “What do you do?” When I was younger, I felt I had to have a simple answer to that or I’d seem like a fucking jerk.

People want to see you doing just one thing to believe that you’re serious. The question is always “What do you do?” When I was younger, I felt I had to have a simple answer to that or I’d seem like a fucking jerk.

Especially because, as an artist, the most necessary thing is to keep moving and exploring if you feel boredom creeping in.

Absolutely, which is why I never tell people anything anymore. When I was younger I’d get so excited to tell people what I had in the works—I’d say “Oh, yeah, I got this coming up and I got that coming up,” and then if it didn’t happen somehow, I looked like a liar and I’d feel terrible about myself.

It’s hard because if you’re excited about something, you want to talk about it. But it can be dangerous.

You never know if people are hating on you, once you’ve said something like that. Especially if what you tell them about doesn’t happen.

I learned that. You just can’t tell people what you’re doing. It’s kind of like the evil eye, you know? Words are active, they’re actions, and if I talk about something before its fruition then it can be killed. Someone can almost curse you if you tell them what you’re working on.

It’s actually something inherent to the English language. I was reading recently that

The English language has a lot of spells within it and was constructed with and for invocations. So you’re casting spells just by talking.

The English language has a lot of spells within it and was constructed with and for invocations. So you’re casting spells just by talking.

I have a friend who is so paranoid that he doesn’t even tell people if he’s traveling somewhere on Friday, for example.

Oh, I don’t either. There’s more power in being discreet.

And it’s true. It can happen. Especially in a place where you’ve got your things sorted. It’s bad news to have people invading that very private kind of space.

Guston said this thing once, about never painting until everyone leaves the studio—because once somebody’s in your space, you have to put up a shell in order to be social. But when everyone leaves, you become your real self. Actually, what he says, which is so great, is that once everyone leaves, then he leaves, and that’s when the magic happens. That’s when the painting happens. In that sense, painting is a religion. I mean I do this every day. I come here every day and paint. This is where I find a lot of my answers to questions in life. And once you’ve “left” the studio, that’s when you can let God take over. And now, God is working through you to manifest these pictures.

It’s a devotion, in that sense. Almost monastic.

I mean some people like to have other people’s energy around for their work, they like a little party atmosphere. But I’m thirty-two now, I think that I’m past the era of parties in the studio. I’ll party with close people, just to get in different zones. Sometimes that helps for the pieces, to see what comes from being in different mind states. People say that the truth comes out when you’re intoxicated, and it can help me be impulsive. It’s a good way to keep my mind from taking too much control over a piece, because it’s your mind, your body, and then your soul—the soul is the top. Your mind will keep running off if you let it, so you have to control it.

I was just reading this book called “

It’s a science, basically—I love that.

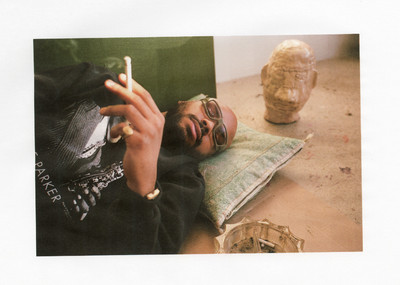

Everything is a science, an alchemy. Even making paintings. You take these mundane materials like paints, brush, canvas, and you make these magical tablets that have all this information, and all this history.

Everything is a science, an alchemy. Even making paintings. You take these mundane materials like paints, brush, canvas, and you make these magical tablets that have all this information, and all this history.

That’s the humbling part too—the act of creation is never even fully your own. You’re just a part of this ancient alchemical process.

Which is something else I love about painting—it hasn’t really changed much. I’m still working with super primal materials. It’s not like music where real instruments are blending with the digital now, or like film, which is almost exclusively digital. Painting can never go digital. I mean you have digital art, but that’s a different genre. Even when I was making music before and I saw how it was starting to change into digital, I thought “I don’t want to be in front of a computer all day, I want to be in front of real things.” That was another reason I focused on painting in the end, because I love physical objects.

You said magical tablets before, which is so fitting. There’s something magical about the physical object that is a painting. It carries an aura.

It does—and sometimes with my paintings, I even feel I’ve manifested events or situations. I’ll paint something, a room or a landscape, and then a year later, I’ll travel somewhere and I’ll find myself in a place that looks just like the painting.

Almost like déjà vu?

I feel it’s more of a manifestation.

I think déjà vu and manifestation are on the same plane though. Dreams too, which operate outside of our logical timeframe. Technically, you could experience déjà vu or the feeling of having manifested a situation because you’ve dreamed it already, out of time.

I love that. I feel most of my paintings are dreamscapes at the end of the day. They don’t come from any real place that I’ve necessarily been, but dreams and memories.

You’ve set up the alchemy for perfection but then you allow the instability of life and chance to come into it. Because nothing is ever perfect.

Even artists working in the same medium are going to have different ways of arriving at a finished place.

And in that process, anything can happen. It’s a distilled version of life. You’ve set up the boundaries for those chances and variables.

Yes, exactly. Variables. With the drying period too, specifically with oil paint. I use a lot of oils now and you never know how they’re going to turn out. When you first lay down oil it’s really lush, the colors pop, but then as weeks go by and the oil dries, you start to see things coming out from the last layers. The colors become a little more dull and certain things emerge. This is why you have to take time with your work–if you just finish a painting and send it out the next day, you never know how that thing is going to dry.

It’s still open to nature, at the mercy of natural variables.

Yeah. The temperature of the room, even, can affect it.

Nature always finds a way of humbling you.

Nature always finds a way of humbling you.

Well, it’s a space where imperfections and differences can be seen for their beauty. I was always drawn to art growing up for precisely that reason—it felt like one of the only mediums in Western culture with a pure appreciation of beauty. For example, a white artist can be obsessed with Arabic calligraphy and that becomes a source of beauty, of inspiration. There’s a collective inclination towards beauty in art, whereas in the rest of society we’re taught to hate difference, to fear other cultures.

Do you know

Right, exactly—he found beauty and then let that shape his work, even his perspective. With respect and this very considered practice, it sounds like. Almost research, you could say.

Which is what I’m doing at the moment, too. I’m really interested in the Moors and Moorish culture. So I’ve been researching as much as I can about that.

Moorish culture generally? How did you get into that?

I was fascinated by the fact that Morocco was the first place where they had sidewalks and street lights—even while Europe was still in the Dark Ages. Supposedly, the Moors had learned Kemetic knowledge from the mystery schools of ancient Egypt, by way of the Greeks and Romans. They built universities to study this knowledge and, when they conquered Spain and some parts of Italy, they brought this with them and gave it to the Europeans. Eventually a lot of them were denationalized when the Visigoths defeated them.

That’s true, there are a lot of people in the US with that heritage.

The Moors were even with Christopher Columbus. They’re the ones who guided him over to America, because they were excellent at navigating and had already sailed much farther than Europeans. The everyday Moorish citizen had knowledge of navigation and alchemy and mathematics, unlike today when it’s all so specialized.

It’s easy to control people if you make them specialize. It kind of brings us back to where we started—to this idea that, today, you have to pick one thing to work on—and outside of that you’re just a machine that lives and dies. There’s no room for spirituality, for knowledge, even for discovery. Maybe that’s what studying things like Moorish culture can open us to—operating on that higher plane.

Right. I feel they were really on a higher plane as a people. And that does inspire me, as you say. That’s what I’m looking for. That’s what the search and the work is about.

If Dubois posed a “double-consciousness,” defining it as the strange sense of two-ness, the split-self of the black person displaced in another land becoming “two souls, two thoughts, two un-reconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body,” then, now, it is appropriate to suggest that double has multiplied. We live in a time where there’s cause for the advent of a triple, or quadruple, or perhaps best put, a multi-consciousness. The diasporic black experience is uniquely marked by a permeating sense of dichotomy, between the sense of blackness and the opposing realities and ideals of the society the black person is displaced in. What is of vital interest is the additional layers of consciousness that have arrived with the passage of time, for the children of the second, third or fourth generation, of whom there isn’t the imminent displacement from one to another, only the idea of another place, or the teachings and passings on through previous generations of ideals, myths, religion, and sensibilities. It is strange enough, that one is taught and raised in the African common belief of the unseen, and then lives in a secular West. But, the contemporary phenomenon of multi-consciousness isn’t limited to race or diasporic displacement alone, it is shared by most – we live between multiple realities: the Internet, the television, day-to-day life, the realities of the various ideologies and religions of the present era. Layers of reality that topple over one another, producing a mass state of confusion, and a subsequent search to remedy it. But, the black person, now, perhaps lies at the base of the flame, in an exaggerated chasm, facing the conflicting realities of the contemporary world, and dragging on in a perpetual state of non-belonging that ultimately produces this new, unique form of existence – a surreal existence, which in turn, has led to, in the case of a few chosen artists that represent this new sub-movement in art, a body of work that I want to call New Black Surrealism.