Candyman

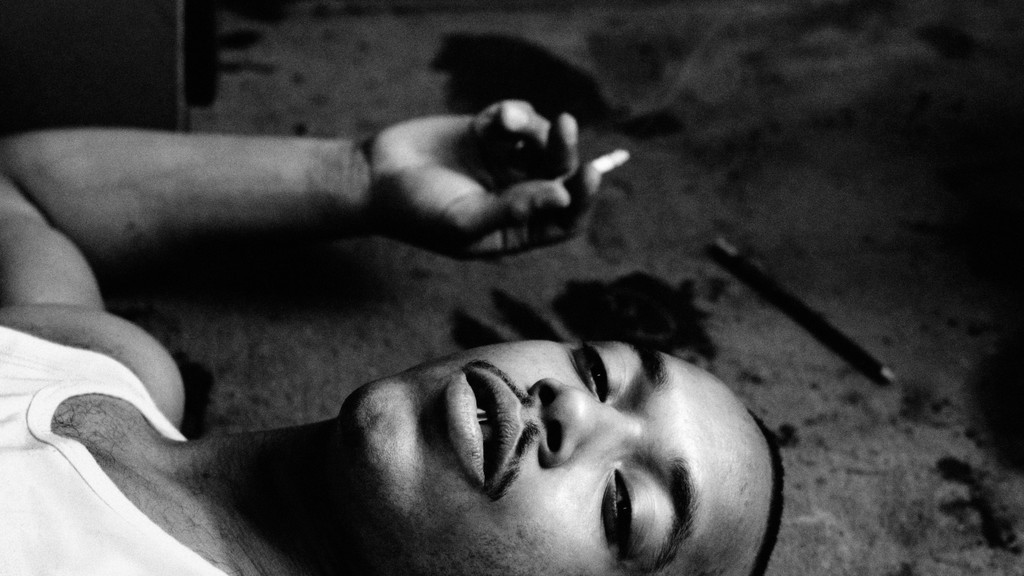

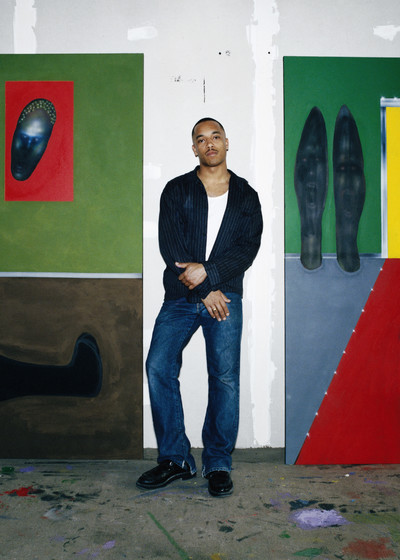

Photography by Larissa Hofmann

Candyman

Photography by Larissa Hofmann

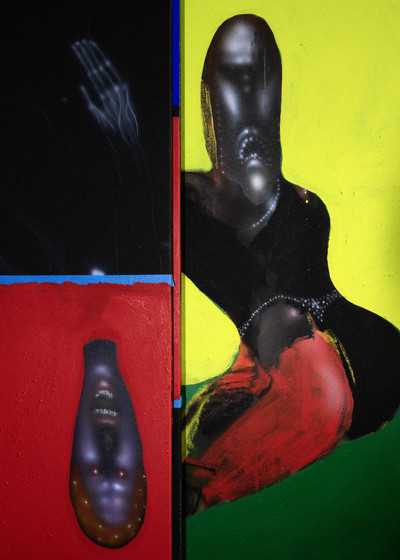

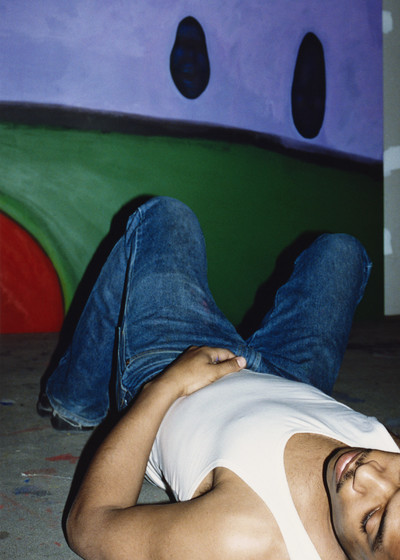

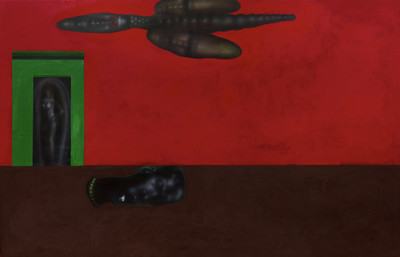

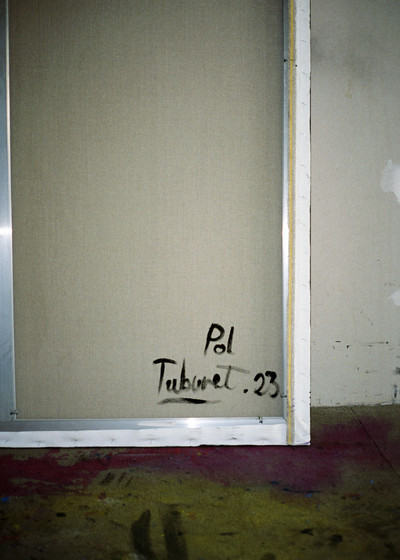

Pol Taburet draws on personal and collective mythologies for his paintings and sculptures. At once domestic and fantastical, his scenes illuminate mysterious, emotional presences lurking behind the quotidian. Spirit-figures and light-bodies twist through brightly colored spaces, at times colliding with recognizable objects to conjure a sense of new worlds, double vision, or dreamscapes. Since graduating from the École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts of Paris-Cergy, he has continuously pushed the boundaries of his material process, combining a medium of alcohol-based paint with oil pastel, acrylic, and airbrushing to float misty figures over dense blocks of color. For his most recent solo show at Paris’s Lafayette Anticipations, “OPERA III : ZOO ‘The Day of Heaven and Hell,’” Taburet staged rooms reminiscent of an unfolding film set, doors and windows giving onto the next discrete scene. In one, cobalt blue wall-to-wall carpeting, indistinguishable from the cobalt blue walls, wrapped protectively around a sculpture that conjured the female form, a fountain-run-dry, an iron spike. The recognizable shape of the gallery space became not only an extension, but also an added layer, of the painted world—continuing the complex correspondence in Taburet’s work between the material realm and a higher plane of perception.

I want to talk about the human figures in your work, which aren’t quite bodies. They seem more like souls or ghosts.

A lot of my work is linked to theory and

It’s not figurative work.

Not at all. They’re alien or abstract bodies—light bodies. Something I find very interesting about Blackness is that it’s a good reflector.

You mean in a physical sense?

Well, I have this very clear memory from when I was young—there was a heatwave in Paris and a family friend had on a pink shirt. His skin was super sweaty and it became completely pink because of the shirt’s reflection. His whole body turned pink.

It takes what’s around it and reflects it, changing it by shining.

Exactly, which moves towards the idea of reappropriation. There’s a big difference between when you appropriate something and when you reappropriate—that’s what I mean by shining too. Even some white people, like David Bowie, for example, made things shine.

He was so fucking beautiful—for me this idea of reflecting and being able to shine is central to what Blackness is. It’s physical but also metaphorical. Black is a color that shines.

He was so fucking beautiful—for me this idea of reflecting and being able to shine is central to what Blackness is. It’s physical but also metaphorical. Black is a color that shines.

That’s so true. You look at someone like Bowie—he’s taking all these elements of different cultures, often, and making them his own.

Obviously there are limits to this, but culture is something that has to be shared and mixed, open to influences. We’re very lucky to be of a generation where we can be here and still see what’s happening overseas at the same time. There’s also this idea of sampling, which is very Black. Like early Kanye creating entire tapes just through sampling. At some point, it all gets reappropriated and often our generation doesn’t even know where it comes from, but we can discover references this way and then go back to find out the source.

It’s a way of reusing something, but flipping it almost. Turning the reference on its head.

Completely, it’s a revolutionary move. You can take Mozart, or something classical, which is completely white music, but when a Black artist like

Sampling is almost a form of revenge. “OK, you’ve taken my culture from me, I’m going to take something back from you. And it’s mine now.”

Sampling is almost a form of revenge. “OK, you’ve taken my culture from me, I’m going to take something back from you. And it’s mine now.”

Re-owning. Exactly.

Sampling as revenge—I love that.

I do the same in my work, in terms of inventing new shapes. I never want to make a painting that looks like anybody else’s—some people see

Yes, I’ve seen it—at the Centre Pompidou.

As part of the white surrealist movement,

So you’re flipping that move, in a way, by taking back from an art historical tradition. Your references are different, of course, but—

They’re different, they’ve been shifted by the digital, which is not as catchable. I think of digital objects—the computer, the phone—as almost ghost objects, because they show you another reality. If you’re looking at a screen and I’m somewhere else in the room, I don’t see what you’re seeing. The screen is like a portal, and when you go through the portal, you’re getting information, information, information, and then boom. What comes out is influenced by that—it becomes about creating new realities, and sampling.

It doesn’t have to be intellectualized or premeditated.

We don’t know what’s going to come out—for you it could be a distorted figure, it could be a Caribbean myth…

Caribbean myth is really interesting in this context, because it’s based on the fact that enslaved people couldn’t use their own cultures or practices or religions. They had to mix it with European Christianity, which created a kind of syncretism. And then you look at

Another sampling. So there’s a long history of sampling as a practice for us. White artists aren’t using this idea as much, because they’re producing a continuation of their own story—which isn’t inherently bad, they just aren’t forced to rework the elements.

Right, because the story is already theirs. They just move it forward.

Which sometimes is very boring, very bourgeois, sure. What I like, and what is really related to Afrofuturism and also to punk, is to counter this with an instinct to erase. It’s an instinct to trash what exists and make something else. It’s like when there was R&B, then you got hip-hop, but then that was erased by trap, and now drill is coming. It’s erasing to rebuild, to create. But you need that moment of chaos first, and I think Black artists are in that moment now. The issue is this situation can easily become dangerous—if you look at Black figurative painting, for example, it just shows a “Black scene” or “Black image,” but it misses the essence of what we can feel or want to show.

That’s precisely one of the things that I want to erase actually—the idea that Black art needs to be so figurative or legibly political. The discussion is always basically, “This is a Black piece against racism.” It’s so reductive and limiting—galleries that once would have excluded artists just for being Black are now including them just for being Black. Ultimately, it’s the same thing. Race is still the motivating factor, rather than the work itself.

Same recipe, different spice. You’re still segregating. There’s this big gallery in Vienna that’s a great example of why this doesn’t work. When the BLM movement happened, there was a realization that the only Black people working in galleries and museums were cleaners or security guards—which actually is a job my mom had. But anyway, there was nobody who had a voice, who could really make change. So, in Vienna, this major gallerist kicked every single employee out and decided to make a “Black gallery,” where they only hired Black people. And to me, it was like “What’s the point? That doesn’t solve anything.”

It’s another example of preserving these racial boundaries, continuing to segregate in a very tangible sense, even while applauding yourself for “change.”

Exactly! Why not create a discussion between people—a mix of employees who can actually have a conversation about what’s happening? Otherwise it just feels like this weird quota that needs to be met.

If you look at what Hollywood is doing right now, it’s exactly that. I find it so frustrating. The whole discussion around a Black James Bond, for example. We don’t need a Black James Bond. Let’s make a new story. Why is it always about substituting Black actors into existing white roles, rather than actually making Black narratives?

Make a new hero! A new mythology. They say human beings are the only species that needs myth, that creates myth. Myths are what allow us to grow and become more aware. So, we need a new story or a real myth from Africa—not some dumb Hollywood version like “Black Panther,” which I couldn’t even finish. We need basic fables, like

And sometimes twists on the classics can work, but then make them real twists. Not just replacing a white actor for a Black actor.

It’s not just a blatant attempt to market Blackness. One of the things that interests me so much about New Black Surrealism is that, while Blackness is part of it, that’s because it’s a part of what we experience—but the focus is on the experience itself, the whole experience. So, for example, in Marcus Jahmal’s paintings, you’ll see the figure of a cop because that figure is in the shared subconscious. But it’s not a cop shooting someone, or an attempt at a BLM message. It’s not a political message at all. What’s so strange about this pressure to be political is that it almost denies a variety of Black subjectivities. But as a Black artist, you can still have a soul and have an individual experience that isn’t necessarily part of this larger stamp of Blackness all the time.

Yes, and this stamp at some point becomes branding. I thought about this when I went to Art Basel Miami a few years ago. There was this huge hype around Black figurative painting, right? When I got there, I was focused on setting up my booth—I didn’t look at anything else, just installed my show, which, by the way, had no Black people in the paintings. None. Because I didn’t feel the need to do that. But when I finished and looked around, I saw that all the other booths were full of huge figures of Black people—Black bodies and faces. And when I saw that, I had this shocking realization: the art fair becomes a market. It was a market in the South still selling Black people. At first I thought, “Well, but it’s helping Black people create, giving them money, etcetera,” but then the more I looked around, the more I realized it was only white people selling this work. They were still benefiting. For me, there’s always this back and forth—I never really know how to feel about the Black figurative movement.

Black figurative painting was branded. Let’s find somebody that can do that for New Black Surrealism, which can be a kind of reunion, a making of a generation and a history.

Black figurative painting was branded. Let’s find somebody that can do that for New Black Surrealism, which can be a kind of reunion, a making of a generation and a history.

Also, because it often has no real sense of interiority or subjectivity.

Exactly—there’s no epiphany or transcendence, which is essential. Simply presenting Black bodies in this way, to me, feels like those early colonial photographs that were used as advertisements in Europe, to show Africa and the people there. Very anatomical images of bodies. I think more artists should be on this surrealism vibe you’re talking about, precisely because it lets you move past this white point of view that can really kill a work. Show me the inside of your brain, you know?

Show my Black subconscious, not my body, not my skin. The market will still try to brand that subconscious of course, but it will be more difficult to do. It should be a movement—there aren’t enough Black movements in art, hardly any actually. We need that. New Black Surrealism is a movement, at least.

We do. Black figuration started with Kerry James Marshall. Then you had Noah Davis, all those artists and boom,

Yeah, exactly. An alternate history—that’s punk, you know. I’ve always loved the idea of Black punk. Bad Brains, etcetera. But it’s hard to do that right now, because if you’re a Black artist at the moment you’re really incentivized to make certain things. To put a cop in a painting—but that’s still just a response to a white world. It’s not about the mind. It’s secondary. Don’t get me wrong, the risk of being stopped by the police is part of my life. Work that confronts that has a purpose—it just isn’t everything. Even when I write, people always want to preface it by saying I’m a Black Muslim. They brand me.

It makes people more comfortable, because it’s a way of understanding why you’re saying certain things.

It diffuses the message, actually, because then someone can say “Oh, yes, this is a Black artist so I know what that’s about.” They don’t actually have to confront the work.

And really, where you grew up, what your personal lived experiences are, those things are all way more important to who you are than your race and religion. It makes me think of this movie I really love, “

A swarm has no shape, no color, no gender. It’s one body, but hundreds of bodies at the same time. I think about this a lot in my work as a way to resist the idea of the “Black body”—finding a shape that is unshaped, that can grow and move.

A swarm has no shape, no color, no gender. It’s one body, but hundreds of bodies at the same time. I think about this a lot in my work as a way to resist the idea of the “Black body”—finding a shape that is unshaped, that can grow and move.

The swarm is related to the idea of sampling too, because the resample is you, it’s the physical body in this case. That really resonates because for so many of us, there are all these points of reference in terms of where we’re from, what cultures we belong to, etcetera. I’m a resampling of Egypt and Eritrea and MTV, even. At what point does it meet and what kind of swarm does it create—that becomes the question.

Focusing on identity segregates so quickly. It’s a trap. We’re trapping ourselves in these small things when the experience of humanity and the soul is so much more. I want to show you violence with some pleasure, for example. It’s that simple and that universal. If I want to show you a flower, I can show you a flower the way I see it. Maybe my past history or trauma informs how I, in particular, see that flower, which changes how I paint it—it might make it a more powerful painting. But the painting itself isn’t about that trauma. It’s about conveying this image and moment that is interesting to me. When I paint people, or ghosts, for example, sometimes I include violence—but actually, in my work, mostly nothing is “happening,” exactly. It’s people in spaces of color. That’s what I’m drawn to: the colors of a room, the situation. It’s not premeditated. People always want to read into things, to point out that an artist must have put a line there for this reason or a color here for that reason. But painting is never that mathematical, logical. It can take months in my mind to think about a painting and then when it comes to confronting the canvas sometimes it never even works. In my mind it’s perfect, but then I have to grapple with the fact that I’m dealing with a physical object. It can never be the vision in my head. My most beautiful painting will never exist.

But don’t you find that moment of needing to let go freeing? There’s all the planning and thought, but as soon as you start making something it becomes so fucking free.

It is freeing, yes. And it can never go according to plan because it depends on the smallest things: your mood, what you ate, what you drank, how many cigarettes you smoked. Sometimes I just smoke cigarettes in front of a canvas for hours because I’m scared to start. I fail and fail and fail, but finally it all works because of that failure, because of how scared I was to do it for so many days. The mistakes are what make it work.

Mistakes make it.

Mystic mistakes. Yes, like it’s coming to you from another world.

Channeling.

It does feel like channeling, yes. You never know when something good is going to come. It’s like looking for the blue notes in jazz—everything shifts and then starts to take shape. You have to try to attract it. You have to be open to it, always.

If Dubois posed a “double-consciousness,” defining it as the strange sense of two-ness, the split-self of the black person displaced in another land becoming “two souls, two thoughts, two un-reconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body,” then, now, it is appropriate to suggest that double has multiplied. We live in a time where there’s cause for the advent of a triple, or quadruple, or perhaps best put, a multi-consciousness. The diasporic black experience is uniquely marked by a permeating sense of dichotomy, between the sense of blackness and the opposing realities and ideals of the society the black person is displaced in. What is of vital interest is the additional layers of consciousness that have arrived with the passage of time, for the children of the second, third or fourth generation, of whom there isn’t the imminent displacement from one to another, only the idea of another place, or the teachings and passings on through previous generations of ideals, myths, religion, and sensibilities. It is strange enough, that one is taught and raised in the African common belief of the unseen, and then lives in a secular West. But, the contemporary phenomenon of multi-consciousness isn’t limited to race or diasporic displacement alone, it is shared by most – we live between multiple realities: the Internet, the television, day-to-day life, the realities of the various ideologies and religions of the present era. Layers of reality that topple over one another, producing a mass state of confusion, and a subsequent search to remedy it. But, the black person, now, perhaps lies at the base of the flame, in an exaggerated chasm, facing the conflicting realities of the contemporary world, and dragging on in a perpetual state of non-belonging that ultimately produces this new, unique form of existence – a surreal existence, which in turn, has led to, in the case of a few chosen artists that represent this new sub-movement in art, a body of work that I want to call New Black Surrealism.