Doors

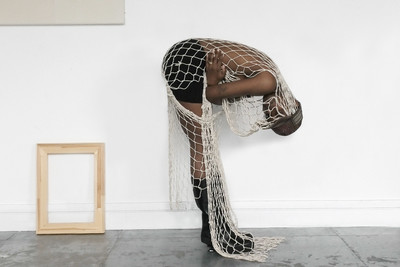

Photography by Benedict Brink. Styled by Jawara Alleyne.

Doors

Photography by Benedict Brink. Styled by Jawara Alleyne.

Rhea Dillon describes her work as a “research-based” practice, which barely scratches the surface of her immersion in the archive of the Black diaspora and critical theory. Drawing on references as diverse as the poetry of Édouard Glissant and bell hooks, to the thought of Stuart Hall and Françoise Vergès, and the cults surrounding figures like Donald Trump and Jeffrey Dahmer, Dillon produces visual art, poetry, and installations that question the “rules of representation.” Her carefully executed pieces are densely layered with references and critique: histories overlaying poetry overlaying personal narratives to produce a geology of meaning. Recent shows, like “An Alterable Terrain” currently at Tate Britain, London, have expanded on her interest in the formation of British and Caribbean identities as well as her investigation of the exploitation of Black female bodies.

We’ve been talking about titles.

Titles of my work, yes. You mentioned Deana Lawson.

There’s one title of hers that I find super interesting—she took a picture of a hole in a couch at a strip club and called it “

That is interesting, that ‘African-French’ isn’t a term we use.

I was talking to Saidiya Hartman about this—how these terms were arrived at, and why they’re so heavily practiced—especially when it comes to America. I have a lot of friends who say that they are Black American instead of African American, others who only say African American. It’s about the desire to place power onto linguistics itself. Saidiya mentioned that a lot of university courses in the US are changing their title from ‘African American Studies’ to ‘Black Studies’. That was quite cool to me as it signals this shift from thinking only about the New World—and taking that to be singularly American—to having a more global capacity. I’m excited by that.

It’s interesting to start thinking very intentionally along those lines. Because traditionally these terms get used and then those labels just stick—it’s not really conscious, just like the way Native Americans were called Indians for centuries.

The idea of a ‘Contemporary African’ sounds wild, but that’s kind of what we’re talking about.

The idea of a ‘Contemporary African’ sounds wild, but that’s kind of what we’re talking about.

In America, in particular, there’s also this sense of the Other continuing to be ‘new’ because they don’t actually have African immigrants in the same way that Britain or France does. I think that must influence these perceptions in a subtle way.

There are African immigrants, but perhaps fewer than in Europe. But I think you’re right in so far as Europe has this disengagement that happens when old meets new, whereas America just has the new.

Exactly. And we have our lineage, at least somewhat.

We have the contemporary generations versus only being able to say “I’m a descendant of…”

Yes. I talked to Marcus Jahmal about this actually, because of the heritage inherent in his name: Marcus. Jahmal.

[laughing] Marcus. Jahmal. Exactly!

And that took us on a whole spin because he has a real, almost unconscious fascination with the Moors. It’s a longing that influences a lot of his work. Obviously, there was a lot of Moorish movement into the Americas, which is captured in the name Jahmal, and that made me think about a kind of blood memory or an unconscious memory that ties us. Of course, I’m sure not every Black American has this kind of longing—

Or desire.

Right. On the one hand there’s someone like Marcus who does have that desire, but on the other I’m thinking of that scene in “

“I ain’t no African.”

Exactly! And it’s true, in the end. Africans in some countries don’t see Blackness in the same way either—some might look at Black British people and say they’re not African. They’re Black.

Sure, but then we’re fighting from within ethnicity, and nation, right? Nation is a concept that I have so much difficulty with because I feel that to formulate a nation is to use the master’s tools. Jamaica has such a commitment to being a nation, for example, but I’m cautious about this—which is why I held a lecture series as a Stuart Hall reading group called R.I.E.N. (Race, Identity, Ethnicity, and Nation). I’m still figuring out what the desire for a nation is, outside of a desire to create a potentially fascist Black Republic.

I mean there’s always a natural inclination, even within a small place, to have some group that’s slightly different from another. In Ethiopia, for example, you’ve got the Tigrayan people and there’s always going to be some—

Differentiation. Right.

Well, it’s a deception because it satisfies the sense of belonging that people are so desperate for.

There’s a need for security in that desire for belonging. It feels good to know where you’re from. It’s like when people do an ancestry test and then they can say “I’m Nigerian and I’m this and I’m that.” But the thing is, ancestry.com doesn’t understand that you’re only Nigerian insofar as your tribe was in Nigeria for some period of time. Do you know what I mean?

You can carry souls more than you can carry blood. One is lighter than the other. Potentially. Depending on how troubled your souls are.

You can carry souls more than you can carry blood. One is lighter than the other. Potentially. Depending on how troubled your souls are.

I really do, because I don’t personally have any sense of belonging to a nation. I could say I’m Egyptian and Eritrean. But it’s a romanticized myth, because I go back there and quickly realize that I’m not from there. It’s my blood and I have that connection, but I don’t think I could live there. So already there’s a split between those two places, and then even in England, where I grew up, I don’t feel English. That continuous, generational movement makes you lose your sense of belonging. You’re always looking to arrive somewhere, but it’s an illusion to connect belonging to a place or a nation or an ideology. That question of belonging would be far better satisfied by something more eternal, which is why I’m more concerned with the soul and the unseen.

The soul and the unseen: exactly what I was going to say. You mentioned blood, and I thought back to souls—souls have more prescient weight here. Blood thins, blood changes, and the colonizer’s blood runs through us because of rape and pillage. But souls can’t be ignored. So thinking through souls just makes things more honest and more able to be carried, right? You can carry souls more than you can carry blood. One is lighter than the other. Potentially. Depending on how troubled your souls are.

Yeah, troubled souls, certainly. Earlier you said “when we arrive at blackness, we often arrive through death.” That this feeling is shared across so many different contexts and places. You could see it as a path on which this collective soul or the collective conscious has set out, to try to arrive at an understanding. It’s a feeling that connects far more in this case than a place or nation.

Which takes us to your prompt of ‘New Black Surrealism’—and also to the language and titling of my own works. A number of the titles—I wouldn’t say a majority, but a number—are instigated by a past artist, writer, etcetera and my belief that there can be shared remembrances across souls. My title

Rhea Dillon, The Myth Of The Noble Savage, A Hoodlum Afar And A Saint At Her Desk, 2021, 360° dome mirror, Jamaican coins, chain and non drying anti-climb paint, 60 × 60 × 134 cm

That’s very interesting—especially about the hooks parenthetical, because she almost opened up to the unconscious. Whether intentional or not, you as a reader perceived that phrase to be a portal she was opening.

You open a door. And when it’s received, people can go in and open other doors onto new places, which is what’s so interesting about your work. Which makes me wonder, do you think that certain of your works are imbued with a soul? Because I think when you make something—when you truly make it—you infuse something into it. It’s not quite Benjamin’s idea of aura, but that sense of something live being present. For example, in your pieces, the dark reds evoke an emotion immediately, they feel like a portal to me.

My work has soul. There are points when I directly feel like I’m putting souls in the work, certainly. A good example would be my series of spades—those sculpture paintings that are in deep-set mahogany frames and made with oil-sticks. When I’m working with oil sticks, I get really obsessed with the head that forms over the top. I was actually geeking out about this with Anthea Hamilton recently on how oil sticks form a literal skin that you have to peel off to start working with them again. It makes them very human, this skin. I was thinking about that engagement with humanness and the desire to break free from the old colonizer’s debate about what is human and whether Blackness gets to be included in that. When I use oil sticks, I think of them as these souls, the heart of the work, that get situated quite explicitly by me in the piece.

I love that. These are objects that you feel have souls already and those souls can join into the work, in a sense. Are there other examples?

A different version of thinking through souls occurs in

I have a great affinity for performing objects—as a means to perform work without the body. It’s a way of thinking about this hyper-placement of duty and work that’s put on Black and Brown women.

I have a great affinity for performing objects—as a means to perform work without the body. It’s a way of thinking about this hyper-placement of duty and work that’s put on Black and Brown women.

So it’s a release across time and place, in that sense. It’s about souls passing down generations and over oceans.

My grandma was my focus while making this work. She is part of the

The broken glass has so much meaning—and then someone else might bring their own to it too. I guess when you make something, you give it a life that will outlive you, hopefully. And once you give it that, as an object it follows its own life in a way. So, in transit, if it’s breaking apart, if it’s changing, you’re also releasing it into its own life. You made it and now it’s gone.

It’s funny, in terms of making works that exist beyond your time, I had a confrontation with a conservator who freaked out over me using anti-climb paint and newsprint in my paintings.

This desire to make things last forever is futile, anyway.

Yes, and it’s so colonial. I mean, why would I want that? It makes me think of the

You never know what’s going to happen and often beauty can come out of disruption, when nature takes its course—like Greek statues losing their paint. It’s so human to try and resist nature, but we need to embrace disruption.

Exactly. That’s our end quote, ‘don’t fight against natural change!’

If Dubois posed a “double-consciousness,” defining it as the strange sense of two-ness, the split-self of the black person displaced in another land becoming “two souls, two thoughts, two un-reconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body,” then, now, it is appropriate to suggest that double has multiplied. We live in a time where there’s cause for the advent of a triple, or quadruple, or perhaps best put, a multi-consciousness. The diasporic black experience is uniquely marked by a permeating sense of dichotomy, between the sense of blackness and the opposing realities and ideals of the society the black person is displaced in. What is of vital interest is the additional layers of consciousness that have arrived with the passage of time, for the children of the second, third or fourth generation, of whom there isn’t the imminent displacement from one to another, only the idea of another place, or the teachings and passings on through previous generations of ideals, myths, religion, and sensibilities. It is strange enough, that one is taught and raised in the African common belief of the unseen, and then lives in a secular West. But, the contemporary phenomenon of multi-consciousness isn’t limited to race or diasporic displacement alone, it is shared by most – we live between multiple realities: the Internet, the television, day-to-day life, the realities of the various ideologies and religions of the present era. Layers of reality that topple over one another, producing a mass state of confusion, and a subsequent search to remedy it. But, the black person, now, perhaps lies at the base of the flame, in an exaggerated chasm, facing the conflicting realities of the contemporary world, and dragging on in a perpetual state of non-belonging that ultimately produces this new, unique form of existence – a surreal existence, which in turn, has led to, in the case of a few chosen artists that represent this new sub-movement in art, a body of work that I want to call New Black Surrealism.