The Heartbreak Kid

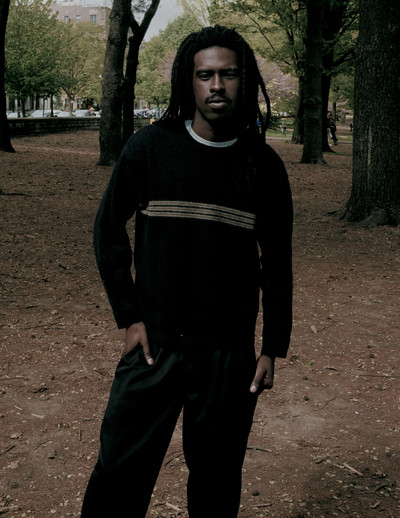

Photography by Michael Wolever

The Heartbreak Kid

Photography by Michael Wolever

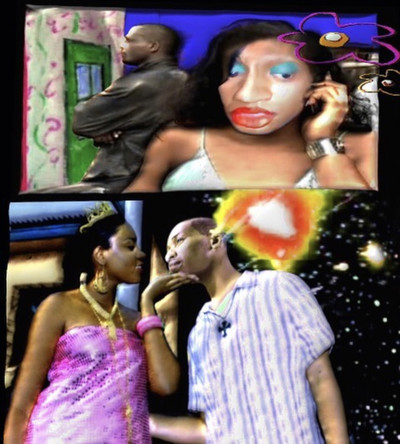

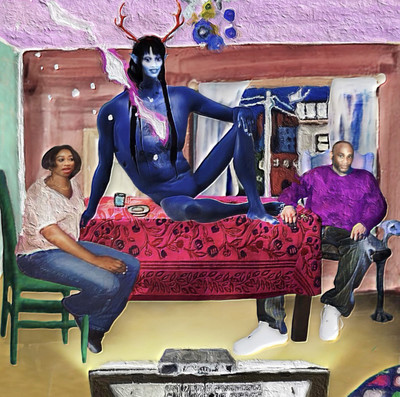

Frank Dorrey is a pioneer of artistic techniques, taking tools for iPhone image editing and using them to create works that challenge traditional categories like collage, painting, and photography. Beginning with photos on his personal camera roll or pulled from the internet, Dorrey distorts space, blurs figures, and transposes recognizable pop-culture objects to create images as enmeshed in contemporary digital reality as much as timeless dreamworlds. Portraits convey personality and mood, even while physical characteristics fade or warp. Community and friendship emerge from gestures and juxtaposition. Bright, joyful colors take on depth and eeriness. Dorrey starts a new piece whenever the mood strikes, and the result is a body of work full of urgency and immediacy—a reflection of a fascination with form, color, and the eddies of the cultural subconscious.

You don’t have a studio, do you? You do your work in the crib, right?

No studio. This is my studio.

And you work off the iPhone only?

That’s my main thing. The foundation of everything is put together there. I use a bunch of apps—Pixar, which is basically Photoshop for the iPhone, 3D This, which adds textures to photos, stuff like that. Then I take the results and print them on canvas.

I feel Instagram is the new gallery.

I feel Instagram is the new gallery.

Do you see yourself playing with any other mediums some day?

Maybe painting, but it’s not my favorite thing.

Honestly, I like that you’ve embraced technology to produce these—they’re a new kind of painting, actually. They’re unlike anything that’s ever been done before. I love that you don’t have a gallery either—you’ve just got your IG and you sell prints from there. You’re avoiding the whole gallery system.

It’s true. You can skip the process and you’re not afraid to do that. When did you start working in this way?

I always edited photos—even in high school, I would take a picture of myself or a photo that I found on Tumblr and mess with it. Just bored in classes, making stuff. Then it evolved from there as I started experimenting more, using digital interpolation to scale images up, etcetera.

You went to high school in New Jersey, right?

Yes, and then I went to Minnesota for my senior year. It was a weird transition because I had to be a new kid in that last year of school. But I found people in my life that really taught me—like my art teacher, Mr. Gaskins. He was brilliant. He used to tell me about a lot of mythological Greek stuff, like

In the space of my work there are no words, there’s nothing tangible to really attach yourself to. That’s where I think I can get at something like a collective understanding.

In the space of my work there are no words, there’s nothing tangible to really attach yourself to. That’s where I think I can get at something like a collective understanding.

And then you moved back to Jersey?

I moved back to Jersey right after Minnesota and started working as a busboy. And making my pieces.

I’ve been thinking about what Dubois called “double consciousness” recently—how today we have triple consciousness, quadruple consciousness even. Do you feel that split existence comes into your work?

100 percent, because

What movies off the top of your head do you like? Books, other references?

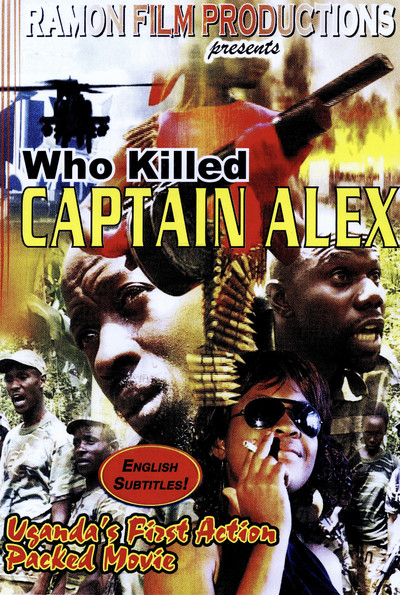

A lot of Rom-Coms. Like this one movie with Ben Stiller,

The images don’t come from dreams, but they do feel like they come from somewhere beyond me. They just pop up and I can’t explain why or where they’re from, you know?

The images don’t come from dreams, but they do feel like they come from somewhere beyond me. They just pop up and I can’t explain why or where they’re from, you know?

I really feel your work comes out of a new kind of existence. The pieces are like hyper-contemporary dreamscapes. You’ve scoped out all these daily images, but then put them into this other world. Does that stuff come from your dreams?

The images don’t come from dreams, but they do feel like they come from somewhere beyond me. They just pop up and I can’t explain why or where they’re from, you know?

There’s stuff that seems pretty spirited about it. Do you feel possessed almost?

[laughs] In the most beautiful way, for sure.

In a good way, I mean!

I mean, in terms of spirit coming through, I grew up in the Church, but I felt detached from a lot of those beliefs. I can’t help it though; those things stick with you. I do recognize there’s something higher, but explaining what that is has always been a battle for me.

I’m realizing that every time I go through those really bad moments, I come out of it finding new ways to love.

I’m realizing that every time I go through those really bad moments, I come out of it finding new ways to love.

I can feel that tension you’re describing in the pieces. It comes through, it does. The work has got this real lightness to it, but it’s also super dark at times, which is one reason I love it so much. I don’t know, as I keep getting older, it all seems to be getting darker.

It gets brighter too, the light definitely gets brighter.

Eventually, I hope it does. It definitely goes in and out, I feel.

I was feeling that way last night—just super destroyed. But I’m realizing that every time I go through those really bad moments, I come out of it finding new ways to love. To me that’s the craziest thing, because no matter what, you always discover something new.

If Dubois posed a “double-consciousness,” defining it as the strange sense of two-ness, the split-self of the black person displaced in another land becoming “two souls, two thoughts, two un-reconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body,” then, now, it is appropriate to suggest that double has multiplied. We live in a time where there’s cause for the advent of a triple, or quadruple, or perhaps best put, a multi-consciousness. The diasporic black experience is uniquely marked by a permeating sense of dichotomy, between the sense of blackness and the opposing realities and ideals of the society the black person is displaced in. What is of vital interest is the additional layers of consciousness that have arrived with the passage of time, for the children of the second, third or fourth generation, of whom there isn’t the imminent displacement from one to another, only the idea of another place, or the teachings and passings on through previous generations of ideals, myths, religion, and sensibilities. It is strange enough, that one is taught and raised in the African common belief of the unseen, and then lives in a secular West. But, the contemporary phenomenon of multi-consciousness isn’t limited to race or diasporic displacement alone, it is shared by most – we live between multiple realities: the Internet, the television, day-to-day life, the realities of the various ideologies and religions of the present era. Layers of reality that topple over one another, producing a mass state of confusion, and a subsequent search to remedy it. But, the black person, now, perhaps lies at the base of the flame, in an exaggerated chasm, facing the conflicting realities of the contemporary world, and dragging on in a perpetual state of non-belonging that ultimately produces this new, unique form of existence – a surreal existence, which in turn, has led to, in the case of a few chosen artists that represent this new sub-movement in art, a body of work that I want to call New Black Surrealism.