Yawar Mulku Will Be Televised

A look back at how a Bolivian film from 1969 influenced reality, and what it can teach us about the power of reclaiming control of the dominant narrative in the age of post-truth politics.

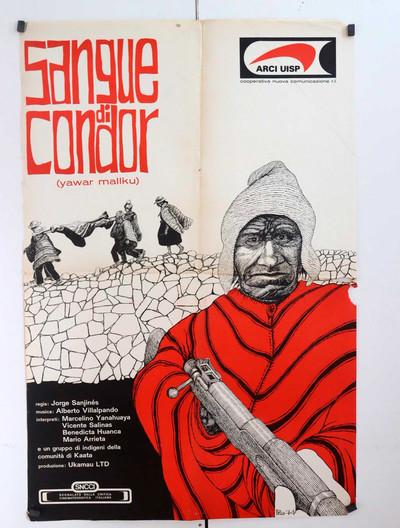

In Jorge Sanjinés’ Yawar Malku (Blood of the Condor), Ignacio visits a medical clinic in his Indigenous Bolivian community, seeking help for his wife who is struggling to conceive. What he uncovers is a horrifying reality: the Progress Corps, operating under the guise of providing healthcare, has been sterilizing Indigenous women without their consent. The camera captures Ignacio’s silent realization as his world collapses—his wife, too, has been a victim. This is the crux of Yawar Malku, and the cinematic moment that triggers an uprising, both on screen and off.

Released in 1969, Yawar Malku has never been easily accessible. It was not distributed on home video and is rarely screened in cinemas. Indeed, when it was first released, the Bolivian government actively suppressed it, so Sanjinés traveled across Bolivia with portable projection equipment to screen it for rural communities, many of which had never before experienced cinema. And yet, despite this relative obscurity, Yawar Malku sparked debate and outrage, and ultimately influenced Bolivian politics, making it one of the rare films that altered the course of history.

Emerging from the revolutionary 1960s, Yawar Malku is a product of the Third Cinema movement, which rejected the capitalist, neo-colonial conventions of Hollywood. In Towards a Third Cinema, Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino argue that Hollywood’s spectacles reinforce the status quo, offering escapism rather than meaningful critique. By contrast, Yawar Malku disrupts this system. Its documentary-style realism blurs the line between fiction and fact, embedding itself in the socio-political consciousness of its audience.

Indeed, to many Bolivian people, Yawar Malku did not feel like a film, but a mirror of their reality. And many have argued that this was no fluke, but the result of Sanjinés’s cinematic decisions. The opening title card sets the tone of this careful construct, displaying a quote from Nazi official Martin Bormann declaring that the oppressed “need no medical attention” and should be left to “abort as often as possible.” From that moment, the audience is thrust into a world where the unspeakable becomes plausible — not merely fictional but part of a historical pattern of genocide. By blurring the line between the conceivable and the real, the film’s political critique makes its claims feel uncomfortably true. Moreover, the cinematography has the feel of raw reportage, as though it were capturing events in real time rather than constructing a fictional world. One powerful scene shows Paulina, an Indigenous woman, participating in a coca leaf ceremony, a nearly one-to-one recreation of the ritual the crew performed to gain the trust of the Quechua-speaking community — whose members, in turn, were cast as versions of themselves. In another sequence, Progress Corps representatives (thinly veiled stand-ins for the U.S.-financed Peace Corps workers active in the region at the time) distribute Western-style clothing to Indigenous women, attempting to draw them into the clinic. The gesture is hollow, an attempt to impose Western values thinly veiled under the guise of charity and progress. This theme of cultural domination is further explored through language, as an affluent Bolivian mother speaks to her children in English — a privilege denied to the Indigenous population. These scenes illustrate how the film critiques not just medical atrocities, but the broader forces of classism and imperialism. And, indeed, some defend Sanjinés’s depiction of the sterilization programs — later proven to be fiction, not fact — as a metaphor for the broader cultural eradication of a people.

By infusing such frustrations with bureaucracy and capitalism into its narrative, Yawar Malku made the shocking seem plausible. This realism bolstered the film’s propagandistic effect, and in a Bolivia already suspicious of Western involvement, the film’s accusations struck a nerve. The reality was more complex than the film suggested. There was no large-scale sterilization program orchestrated by the Peace Corps, and while evidence later emerged that some Peace Corps volunteers had inserted IUDs into Indigenous women without proper consent, these were scattered examples of malpractice largely due to language barriers, rather than a broader genocidal conspiracy. The ethical stakes that the film raised are complex: if fiction can incite such belief and action, what responsibility do filmmakers bear in shaping the narrative, especially when that narrative closely resembles real life? Does art have a duty to the truth, or does it serve a higher cause in confronting power?

These questions became especially potent as the film gained traction, contributing to a national response that mirrored the revolt of the movie’s fictional community. The film sparked an uproar about Western interventionist policies. People gathered in organized protests, marched in the streets, and held public forums and discussions that were often covered by the media, to demand that their government address the issues portrayed in the film. Indigenous and rural communities in particular saw Yawar Mallku as a reflection of their own grievances and pressured the government to act. Eventually, President Juan José Torres’ leftist government launched an investigation and expelled the Peace Corps from the country entirely.

What makes Yawar Malku remarkable is that it didn’t merely reflect the growing anti-imperialist sentiment of the time—it shaped it. Indeed, following in the wake of the film, widespread mistrust of birth control spread across the region, and in the following decades, Bolivian nationalism exerted itself in problematic ways, including through greater control over women’s bodies. Distrust of foreign-sponsored birth control programs led to government restrictions on contraceptives distributed by foreign organizations, with Bolivian leaders emphasizing the need for national control over family planning programs. The government framed reproductive health as a matter of sovereignty and cultural preservation. By the 1970s and 1980s, this perspective led to restrictive policies on contraception access, particularly in rural and Indigenous areas where mistrust was highest.

Today, the film’s legacy is fraught with contradictions. On the one hand, it inspired a wave of Indigenous nationalism and decolonial sentiment; on the other, it perpetuated myths that had lasting, and at times harmful, consequences. Fiction, as much as fact, can shape public perception. This intertwining of fact and fiction, of representation and reality, underscores the fundamental power of cinema as propaganda. Sanjinés thus illustrated an age-old principle that has been marshaled by revolutionaries and authoritarian regimes alike: the act of controlling images is as much a tool of power as the military or the police.

As we find ourselves in a new age of both media manipulation and digital censorship, the lessons of Yawar Malku are more relevant than ever. In a world of social media platforms and post-truth politics, a world where racist rhetoric can supposedly be backed up by “video documentation,” but also where international atrocities are often only revealed when first-hand accounts or footage are released on non-conventional channels, the question remains: who controls the narrative? And what is their relationship to truth? The veil between reality and fiction has been worn thin. Yawar Malku reminds us of the power and political impact of narrative — illustrating both sides of the ethical issue of seizing control of the story.

In 1969, the decolonial revolution was rarely televised. But history, as Yawar Malku shows us, has a way of finding its own lens.

The Revolution Will Be Televised

AA:

what does the revolution will be televised mean to you

Chat GPT:

The phrase “the revolution will be televised” originated from a 1970 song by Gil Scott-Heron. It suggests that the struggles for change, especially political or social revolution, would be broadcast on television—though not in the way activists or revolutionaries might hope. Instead of being directly engaged in or informed by the grassroots movements, the media would likely sensationalize or commercialize the event. It captures a tension between the authenticity of grassroots struggle and the way it might be mediated or controlled by mainstream media.

To me, the phrase also speaks to the idea of spectacle in activism—how movements might be commodified or reduced to entertainment or soundbites when presented through media. It’s a reflection on how technology can both connect people and distort the realities of social change.

AA:

no, gil scott heron said the revolution will not be televised

Chat GPT:

You’re absolutely right—Gil Scott-Heron’s poem/song “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” actually emphasizes that real, transformative social change won’t be captured or sanitized by the media. It warns against the idea that media coverage will authentically represent or convey the true nature of a revolution or movement. The revolution, in Scott-Heron’s view, will be a grassroots, lived experience, not a spectacle for consumption or commodification on TV.

The phrase “The revolution will be televised” is often used ironically, referencing the disconnect between the real struggles of revolution and the way they are typically portrayed by mass media, which can dilute or distort their meaning. So, when people say “the revolution will be televised,” they may be acknowledging that, while media will likely cover it, it will never truly capture the raw, genuine heart of a revolutionary movement.

It’s a critique of the media’s role in shaping narratives and a reminder that meaningful change happens beyond the reach of spectacle.

AA:

so what would the revolution WILL be televised mean to you

Chat GPT:

“The revolution WILL be televised” flips the original idea on its head. If we take it literally and in a contemporary sense, it could suggest that social movements or revolutions are now not only covered by media, but actually shaped and influenced by the media itself. In the age of social media, live streaming, and 24/7 news cycles, revolutions and activism are happening in real-time, and the narrative is often driven by the visibility they gain on platforms like Twitter, Instagram, or TikTok.

In this sense, the revolution could be televised (or streamed, or shared) in a way that amplifies voices and causes, helping them to spread globally. However, there’s still the question of whether such media coverage is accurate or authentic. It might be more about spectacle or performative activism than genuine, transformative change.

So, to me, “The revolution WILL be televised” could mean that while media and technology can give revolutions unprecedented exposure, it also raises questions about the impact of that exposure. Is the revolution being commodified? Is it truly transformative, or is it just another trend being broadcast for consumption?