A Cinema of Restless Ghosts

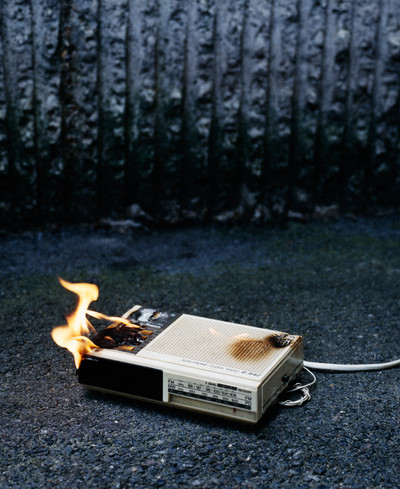

Photography by Larissa Hofmann

Set Design by Sati Leonne Faulks

Creative Direction by Ahmed Alramly & Sid Oudainia Beaulieu

A Cinema of Restless Ghosts

Photography by Larissa Hofmann

Set Design by Sati Leonne Faulks

Creative Direction by Ahmed Alramly & Sid Oudainia Beaulieu

What does a ghost represent? An emotion lingering in the sphere of time? The shadow of a tragedy cursed to echo through eternity? Perhaps it’s the weight of something tethered to a world it no longer belongs to? A ghost is essentially a memory refusing to fade away; a trace of something that once was but is no more. It could be a secret, a sorrow, a story endlessly drifting through eternity waiting to be told.

In Mati Diop’s genre-blending films, ghosts manifest as voices from the past with an unrelenting desire to be heard in the present. Maji, her deceased grandmother in In the Room, begs not to be sent to a nursing home through a voice note; the spirits of migrants in Atlantique (Atlantics, 2019) demand the justice they were denied in life; and King Ghezo, a 19th-century West African ruler in Dahomey (2024), reflects on returning after centuries of isolation and displacement. Despite their differences, these voices share a common yearning, to remember the atrocities of colonialism that continue to affect us in the present day. Mati Diop’s films are revolutionary not through loud proclamations or overt calls to action, but through their ethereal poetry. Diop channels her diverse talents to craft films that give voice to the voiceless.

Like her uncle, Djibril Diop Mambéty, the legendary African filmmaker whose radical storytelling changed the landscape of world cinema, Diop uses the medium as a means to challenge the status quo. She crafts films that transcend cultural binaries, using her rich lineage as a foundation to confront historical erasure, identity, and justice. Yet Diop’s work is no mere continuation of familial legacy. It is a bold, independent response to the contradictions of the modern world. In other words, the legacy she carries does not define her; rather, it informs her singular cinematic voice.

Diop first appeared in Claire Denis’s 35 Shots of Rum (2008), where her subtle performance hinted at the depth of her artistic sensibilities. But acting was only the beginning. Transitioning to directing, her first notable works included the short film Mille Soleils (A Thousand Suns, 2013), in which Mati Diop reconnects with Magaye Niang, the lead actor of her uncle’s iconic film Touki Bouki (1973), forty years after the original production. As Niang attends a screening of the film, his memories of the past merge with his present, creating a moving reflection on time, legacy, and identity. Diop eventually gained international recognition with her debut feature film, Atlantique. A film that made history at the Cannes Film Festival in 2019 as the first feature directed by a Black woman to compete for the prestigious Palme d’Or. It won the Grand Prix and was also shortlisted for an Academy Award that year. The film expands upon, and reshapes the thematic and aesthetic elements of a short film, Atlantiques (2009), that Mati Diop created a decade earlier.

Set in Dakar, Senegal, Atlantique tells the story of Ada, a young woman caught between her love for Souleiman, a construction worker, and the pressures of societal expectations. Like his fellow workers, Souleiman has been unpaid for months. When he embarks on a dangerous journey across the ocean in search of a better life, Diop quite interestingly shifts the narrative to Ada’s perspective. By staying with Ada, the film takes a refreshing angle on the migrant crisis. Rather than focus on the migrants’ journey across the ocean, Diop chooses to remain in the homeland, drawing attention to the communities who are left behind to grapple with the absence of their loved ones.

Diop constantly challenges the Western gaze to create work that reclaims the narratives of Africa by giving us a new perspective on the African diaspora. It’s not what her films are about but rather how they depict these topics that sets her apart from her contemporaries. Her films occupy a liminal space between documentary and fiction, a deliberate choice that allows her to explore her characters’ deepest dreams and longings. This ambiguity is key to her aesthetic philosophy, one shaped by her purposeful use of lo-fi filmmaking techniques to subvert the clean appearance of high-definition cinema. Through this resistance, Diop creates an aesthetic that is uniquely her own, both raw and intimate yet universally resonant.

Consider how she captures the ocean in Atlantique. At the start of the film, the vast expanse of the ocean stretches endlessly, its bright shimmering surface like a portal to another world, distant, hopeful, and full of promise. It represents the dreams and aspirations of those yearning for a better life across the horizon. As the story unfolds, however, the same image shifts in tone and meaning. By the film’s end, the now dimly lit ocean transforms into a haunting liquid burial ground, holding the spirits of those it has claimed. What was once a symbol of escape becomes a dark reminder of sacrifice and loss, an infinite abyss carrying the weight of unfulfilled dreams.

Diop’s work exposes the unsettling truth that the catastrophes of colonialism are not confined to history books, but continue to ripple through the present, shaping systems of labour, mobility, and resistance. In Atlantique, the migrant ghosts return to their homeland to demand justice for unpaid wages. This return highlights the ongoing issues driving migration from West Africa to Europe. Their story connects the economic and social struggles of today to the past, demonstrating how global neoliberal practices and restrictive European border policies sustain the enduring systems of oppression rooted in slavery and colonial domination.

Similarly, in Dahomey, which won the coveted Golden Bear at last year’s Berlinale, the past and present seamlessly converge. This time around, the voice of resistance belongs to a possessed artefact. The film follows the journey of twenty-six artefacts as they are being shipped back to Benin (modern day Dahomey). The voice of King Ghezo, a ruler from nineteenth-century Dahomey, is juxtaposed with the voices of current residents who debate the intentions behind this international act. Their conversation reflects a deep and unresolved tension. For some of the voices, the restitution of the artefacts is a long overdue acknowledgment of historical wrongs. For others, it is seen as an insult, a symbolic gesture that barely scratches the surface of the vast injustices that remain. In the midst of this polarized discussion, a voice rises, calling for more than reparations. It is a call to revolution, a demand for widespread mobilization across Africa to reclaim not only stolen artifacts, but also the right to shape identities free from the shadow of colonial narratives.

This act of restitution is framed not as the achievement of any one individual or government, but as the materialization of bygone revolts. It’s an accomplishment that belongs to energies from the past, figures like Bio Guera, Behanzin, and the Dahomey Amazons. It is as though these historical spirits, once silenced by imperial powers, have returned to reclaim identity. Diop’s work amplifies such cries from the past, compelling us to confront their implications for the present and future. In doing so, she creates a cinema through which the silenced voices of history are finally given the space to speak and the power to be heard.

Diop’s films haunt viewers long after the credits have rolled. Like ghosts, her films are traces, fragments of lives, histories, and emotions that refuse to fade into oblivion. Her work transcends the typical postcolonial narrative by operating between the realms of the living and the dead, the past and the present, the material world and the spiritual, the personal and the political to remind us that Africa’s fight to right the wrongs of colonialism is far from over.

AA:

what does the revolution will be televised mean to you

Chat GPT:

The phrase “the revolution will be televised” originated from a 1970 song by Gil Scott-Heron. It suggests that the struggles for change, especially political or social revolution, would be broadcast on television—though not in the way activists or revolutionaries might hope. Instead of being directly engaged in or informed by the grassroots movements, the media would likely sensationalize or commercialize the event. It captures a tension between the authenticity of grassroots struggle and the way it might be mediated or controlled by mainstream media.

To me, the phrase also speaks to the idea of spectacle in activism—how movements might be commodified or reduced to entertainment or soundbites when presented through media. It’s a reflection on how technology can both connect people and distort the realities of social change.

AA:

no, gil scott heron said the revolution will not be televised

Chat GPT:

You’re absolutely right—Gil Scott-Heron’s poem/song “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” actually emphasizes that real, transformative social change won’t be captured or sanitized by the media. It warns against the idea that media coverage will authentically represent or convey the true nature of a revolution or movement. The revolution, in Scott-Heron’s view, will be a grassroots, lived experience, not a spectacle for consumption or commodification on TV.

The phrase “The revolution will be televised” is often used ironically, referencing the disconnect between the real struggles of revolution and the way they are typically portrayed by mass media, which can dilute or distort their meaning. So, when people say “the revolution will be televised,” they may be acknowledging that, while media will likely cover it, it will never truly capture the raw, genuine heart of a revolutionary movement.

It’s a critique of the media’s role in shaping narratives and a reminder that meaningful change happens beyond the reach of spectacle.

AA:

so what would the revolution WILL be televised mean to you

Chat GPT:

“The revolution WILL be televised” flips the original idea on its head. If we take it literally and in a contemporary sense, it could suggest that social movements or revolutions are now not only covered by media, but actually shaped and influenced by the media itself. In the age of social media, live streaming, and 24/7 news cycles, revolutions and activism are happening in real-time, and the narrative is often driven by the visibility they gain on platforms like Twitter, Instagram, or TikTok.

In this sense, the revolution could be televised (or streamed, or shared) in a way that amplifies voices and causes, helping them to spread globally. However, there’s still the question of whether such media coverage is accurate or authentic. It might be more about spectacle or performative activism than genuine, transformative change.

So, to me, “The revolution WILL be televised” could mean that while media and technology can give revolutions unprecedented exposure, it also raises questions about the impact of that exposure. Is the revolution being commodified? Is it truly transformative, or is it just another trend being broadcast for consumption?