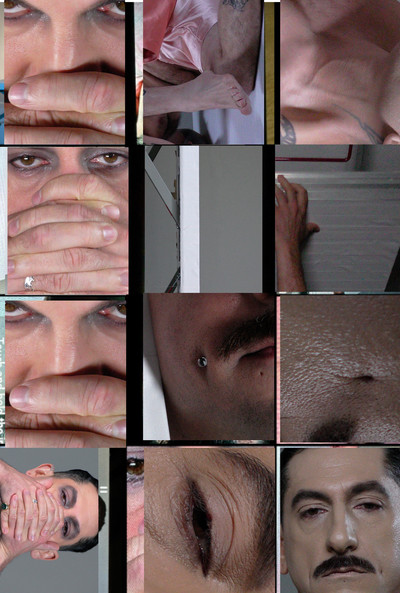

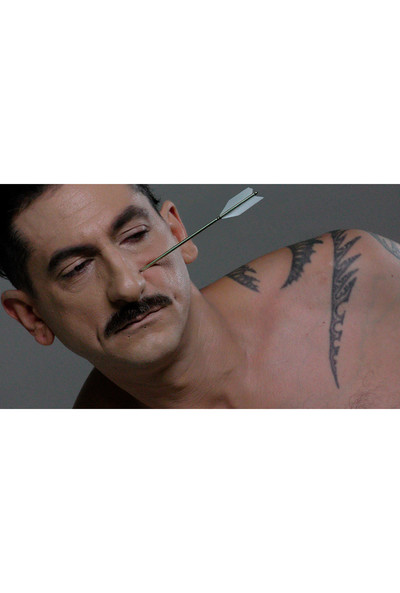

Digital Virtues

Photography by Hendrik Schneider

Styling by Sinisa

Artificial Intelligence by Vittorio Maria Dal Maso

Make-Up by Josh Bart

Digital Virtues

Photography by Hendrik Schneider

Styling by Sinisa

Artificial Intelligence by Vittorio Maria Dal Maso

Make-Up by Josh Bart

As a creative director, Ben Ditto interrogates the boundaries between high and low culture, embracing the subversive, the surreal, and the uncanny. From his role at Dazed Beauty to his eponymous creative studio, Ditto has consistently built upon his fascination with digital phenomena and fringe subcultures — worlds where technology and human behavior collide in unexpected ways. For Ditto, the creative process is as much about exploring the taboo and uncomfortable as it is about producing visually arresting work. Rather than constraining or filtering, he reproduces the digital overwhelm that has become the background noise to our existence, reveling in its chaos.

The revolution will be televised. What does that mean to you?

A point of the original phrase — the revolution will not be televised — was that television represented establishment opinion and ignored everything happening in counterculture at the time. True change would happen outside of the anaesthetising structures created by the mainstream. “There will be no pictures of pigs shooting down brothers on the instant replay” By contrast, now, there will be pictures of “pigs shooting down brothers on the instant replay”. There will be GoPro footage and immersive Apple Vision Pro spatials. Everything is televised and “truth” is more accessible than ever before, but it’s also more confusing than ever. I’m a non-cynical advocate of social media and being online. I’m someone who enjoys the chaos of everything being transmitted directly into your brain. I love it. That’s the standpoint I’m coming from. But I also would say that the idea of a revolution happening now is wishful thinking. We’ve all been siloed into these tiny, polarized groups. There’s no momentum anymore—at least not in the UK or the West broadly. I can’t tell you how many times, over decades of working in culture, I’ve heard someone say, “We’re on the verge of revolution.” It’s not going to happen.

I can’t tell you how many times, over decades of working in culture, I’ve heard someone say, “We’re on the verge of revolution.” It’s not going to happen.

I can’t tell you how many times, over decades of working in culture, I’ve heard someone say, “We’re on the verge of revolution.” It’s not going to happen.

We live in this multi-layered reality now, and it’s almost like having a “double mind.” There’s the world we live in and then this other, layered reality, particularly online. For example, with the conflict in Gaza, social media allowed perceptions to shift in a way that wasn’t possible before. It wasn’t just five or six news channels controlling the narrative — it became a visceral, direct experience through the screen. While it might not lead to a physical revolution, it created this rapid shift in collective perception because people could access raw information in real time from others on the ground.

Yes, and I’ve felt that personally. Growing up in the UK in a conservative, Christian environment, I took it for granted that Israel was in the right about everything. I didn’t question it much and I certainly never understood the UK’s role in creating the problem. Then, the internet happened. At the time, anyone pro-Palestine was either seen as a hardcore leftist or a neo-Nazi. But having seen hours of live footage of brutality, it’s impossible not to empathize with what’s happening to Palestinians. For me, that was a psychic shift. It’s been interesting to feel that happening in myself, especially while also witnessing the whole red pill, 4chan, pro-Trump movement. People talk online about what they call “the noticing,” and I can’t deny that I felt that way about what’s happening with Israel and Palestine. It feels like living in a surreal acid trip where the truth is obvious, but the mainstream media spins it the other way. I can see how people have a moment like that and then think, “Maybe everything I believe is wrong. Maybe Putin is right. Maybe China is more moral than us.” That dissonance is very disturbing.

Noam Chomsky said the best way to control a population is to give them two opposing ideologies to argue over while you sit on top. That’s exactly what’s happening now.

Divide and rule. It’s an old strategy, but it’s incredibly effective. And was certainly a tool central to European colonialism. It’s exactly the way Belgium colonized and ruled Rwanda, for example — they stoked tensions between the Hutu and the Tutsi, which would later lead to genocide.

Divide and rule. It’s an old strategy, but it’s incredibly effective.

Divide and rule. It’s an old strategy, but it’s incredibly effective.

And now social media can amplify divisions — especially when identity politics take center stage in discussions. Do you see it as the same mechanism?

Well, now I think it’s more about how the system always seems to protect itself by diluting movements in order to shift focus. For example, during the Black Lives Matter protests, there was a real surge of awareness about systemic racism and the prison industrial complex. And then it felt like a real shift happened and attention was honing in on black trans rights in particular — which is an important topic to some, but it’s just one piece of a much larger conversation around the core issue of systemic oppression. Then as a result of this, everyone forgets about the main issue. They get distracted, and that’s very convenient for elites.

I find it interesting though, that these patterns repeat constantly. It’s always the same issues just wrapped up differently. I don’t think human nature changes that much.

I mean, I do think that technology is evolving us and we’re evolving with technology in ways that definitely didn’t happen before. Our networking capabilities, integration with algorithms, and now artificial intelligence have a real effect. This kind of superstructure network of technology modifies our behavior in really unpredictable, chaotic ways — and that’s all new. So I think that while human beings are the same biologically as we’ve been for thousands of years, the effects of technology and what that’s doing to us are real in a transhumanist sense.

I think that while human beings are the same biologically as we’ve been for thousands of years, the effects of technology and what that’s doing to us are real in a transhumanist sense.

I think that while human beings are the same biologically as we’ve been for thousands of years, the effects of technology and what that’s doing to us are real in a transhumanist sense.

It’s funny, people will ask me what’s one of my proudest achievements of the year, and I genuinely think it’s this algorithm I’ve built on reels. It’s like that joke: I built this algorithm brick by brick. But in all seriousness, there is this crazy cultural understanding of our world that comes through it — of how we process and understand and take the piss out of everything. Your page does the same thing, I think, it really represents an overview of the Internet and everything on it — from funny memes to political commentary and even extremely violent images. How did you start making that?

My page is an evolution of what I’ve always done, starting from making magazines in the 1990s. I used to sit in libraries, just looking at endless things, making fanzines, and that evolved over time to curating digital culture today. It’s about sharing the chaos — sex, death, violence, humor — everything that unsettles me and affects my limbic system. I love what it does to me, but the real joy comes from experiencing it collectively. It’s like we’re all asking, “What the fuck is going on?” together. I’m fascinated by the relationship between beauty and cruelty.

It’s about sharing the chaos — sex, death, violence, humor — everything that unsettles me and affects my limbic system.

It’s about sharing the chaos — sex, death, violence, humor — everything that unsettles me and affects my limbic system.

I completely agree. I find that all of the most interesting art lives in the middle of that contradiction.

I’m a contradictory person. I’ve always been contrary and like having those two sides to my personality in every aspect. I used to work as a volunteer in a prison, which really showed me that contrast: you feel so much happier about the world when you come out because it’s so fucking horrible in there. Really anything that causes an equal and opposite reaction is very interesting to me.

I chase that feeling too. We’ve grown up in such a contrarian time, maybe more than ever because of the added layers of reality. I’m a Muslim, but I can also be a total degenerate. I fully believe in everything that I believe in, whilst being completely tempted by every other side of myself. I’m just living in this fluctuation and chasing the extent of those emotions — waiting to see if they’ll destroy me or not.

You sound a bit like a Catholic there, talking about temptation and destruction. There’s this constant tension between behavior, guilt, shame, and a greater sense of virtue. That kind of Catholic tension is interesting to me, but my behavior is probably more Protestant; I don’t give in to my vices at all. I haven’t for a very long time. I’m very well-behaved.

To me, sin isn’t necessarily about angering God, but rather wronging your own self and soul; it’s about trying to get from point A to B in terms of the potential of what we are as human beings, and sin being blockers on that path. We have dual natures — angelic and animalistic — and we can choose which path to follow. Kafka said, ‘Evil is whatever distracts,’ which seems right.

I straight up believe in God, unapologetically. People might assume that working in technology and being a techno-nihilist means I’m an atheist, but I fully believe in the wonders of God.

People might assume that working in technology and being a techno-nihilist means I’m an atheist, but I fully believe in the wonders of God.

People might assume that working in technology and being a techno-nihilist means I’m an atheist, but I fully believe in the wonders of God.

That’s interesting. I might not have guessed that. It goes back to the paradox you mentioned.

Exactly. It’s not an act; it’s another tension in my life — being an absurdist while also believing in God. I can’t fully make sense of it. Even so, like you said, I see sin more as someone being unwell. I’ve met people who’ve done terrible things but have also shown moments of beauty. So I believe in God, but not really in the idea of individual evil. Just sickness.

Yeah, and it’s always about actions rather than appearances. What’s going to reduce general pain and suffering? That’s what matters to me.

Exactly. We’ll all be judged by our actions. We can have all the good intentions in the world, but it’s how we go out there and actually behave that truly counts.

AA:

what does the revolution will be televised mean to you

Chat GPT:

The phrase “the revolution will be televised” originated from a 1970 song by Gil Scott-Heron. It suggests that the struggles for change, especially political or social revolution, would be broadcast on television—though not in the way activists or revolutionaries might hope. Instead of being directly engaged in or informed by the grassroots movements, the media would likely sensationalize or commercialize the event. It captures a tension between the authenticity of grassroots struggle and the way it might be mediated or controlled by mainstream media.

To me, the phrase also speaks to the idea of spectacle in activism—how movements might be commodified or reduced to entertainment or soundbites when presented through media. It’s a reflection on how technology can both connect people and distort the realities of social change.

AA:

no, gil scott heron said the revolution will not be televised

Chat GPT:

You’re absolutely right—Gil Scott-Heron’s poem/song “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” actually emphasizes that real, transformative social change won’t be captured or sanitized by the media. It warns against the idea that media coverage will authentically represent or convey the true nature of a revolution or movement. The revolution, in Scott-Heron’s view, will be a grassroots, lived experience, not a spectacle for consumption or commodification on TV.

The phrase “The revolution will be televised” is often used ironically, referencing the disconnect between the real struggles of revolution and the way they are typically portrayed by mass media, which can dilute or distort their meaning. So, when people say “the revolution will be televised,” they may be acknowledging that, while media will likely cover it, it will never truly capture the raw, genuine heart of a revolutionary movement.

It’s a critique of the media’s role in shaping narratives and a reminder that meaningful change happens beyond the reach of spectacle.

AA:

so what would the revolution WILL be televised mean to you

Chat GPT:

“The revolution WILL be televised” flips the original idea on its head. If we take it literally and in a contemporary sense, it could suggest that social movements or revolutions are now not only covered by media, but actually shaped and influenced by the media itself. In the age of social media, live streaming, and 24/7 news cycles, revolutions and activism are happening in real-time, and the narrative is often driven by the visibility they gain on platforms like Twitter, Instagram, or TikTok.

In this sense, the revolution could be televised (or streamed, or shared) in a way that amplifies voices and causes, helping them to spread globally. However, there’s still the question of whether such media coverage is accurate or authentic. It might be more about spectacle or performative activism than genuine, transformative change.

So, to me, “The revolution WILL be televised” could mean that while media and technology can give revolutions unprecedented exposure, it also raises questions about the impact of that exposure. Is the revolution being commodified? Is it truly transformative, or is it just another trend being broadcast for consumption?