No Resolution

In conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist

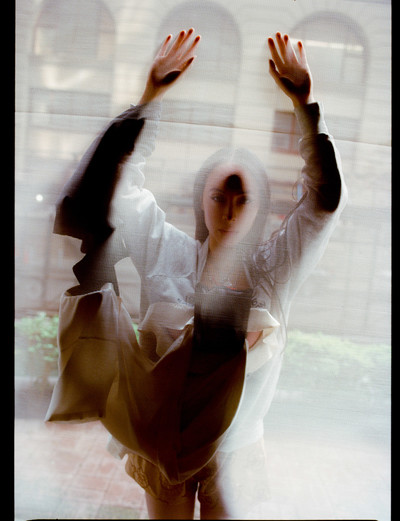

Photography by Joshua Woods

Styling by Andrew Sauceda

No Resolution

In conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist

Photography by Joshua Woods

Styling by Andrew Sauceda

Diane Severin Nguyen’s work is as much about the unseen as what is captured by the lens. Nguyen uses photography and film to interrogate the relationship between objects and the images they project. Her recent trilogy of films navigates personal and political histories, casting performers into roles that mirror broader narratives of power, trauma, and myth-making. Born in 1990 in the United States to Vietnamese parents, Nguyen’s work often reflects her multicultural background and examines the intersections of personal and collective history. From PC music to Italian neorealism and social media semiotics, Nguyen has a magpie-like interest in synthesizing the world around her. Her practice resists traditional readings of violence and memory, preferring to let symbols, objects, and contrasts unfold new meanings. In her work, even the most ordinary materials take on a photogenic life of their own, offering a visceral look at how we construct — and are constructed by — images.

I want to begin with the beginning. How did you come to art or how did art come to you?

Being an artist wasn’t really a possibility for me growing up. But from a very young age, I was obsessed with writing and acting, and that’s where I sought validation. There’s something there about emotions and speaking that I’m still trying to figure out. In high school, I produced the morning announcement, which was basically a daily variety TV show put on by the students. It’s kind of funny relating all this to my work now. Sometimes I think all my art is for teenagers because I still can’t get over how miserable these years were for me. But I couldn’t face it then, so I externalized all my pain outwards, became obsessed with the pain of others, and the systems that allow it to happen. So then I majored in political science and minored in economics and gender, which framed the world through a very exposé kind of lens. But of course, the actual labor of social justice turned out to be menial and didactic, and ideological conviction alone wasn’t enough to overcome the banality of it. But I think because I am always looking for ways to critique power and am someone who identifies with the weak and minor, or the oppressed, photography was the perfect thing to transfer this energy to. It was also a shift from hard power to soft power. Photography is so common, so used and abused, easily re-written and misconstrued. It’s the most democratic medium, which makes it hard to turn into art. The challenge of this was the original turning point.

You spoke about something similar in our first conversation, in terms of the importance of the photographic moment and how a photograph is, in this sense, tethered to the material of its subject, no matter how abstracted the image becomes. Were you drawn to photography, over another medium like painting, because of this?

Yes. Photography cannot be abstract. I’ll stand by that forever. The thing that defines photography is its relationality, first and foremost. It’s about bridging this space between what is considered material art and what is considered conceptual art. Painting always felt too much in dialogue with art history, too accepted as valuable. The possibility of being misunderstood is exciting, and photography is a way to play with that, and in a sense play with the categorizations that separate ‘art’ and ‘life.’

Before you and I met a few years ago, the photographer Torbjørn Rødland described your work to me as very materialist and visceral. It’s something you also touched on in an old interview with Lucas Blalock, saying that your early photographs come ‘out of a desire to juxtapose physical tensions and the failures of their linguistic counterparts,’ especially as this relates to the experience of pain. So I’m curious what it means to you to be making this kind of work in such an increasingly digital age.

I’m not sure I identify as a materialist exactly — it’s more that I see there’s a limitation to language, which always pits the structural against the material. I mean, photography is traumatic, and trauma is photographic, because it’s an act of individuation, isn’t it? Being a victim is about having a physical experience that’s irreconcilable with language. You lose subjectivity, and for a moment, you are framed by an event. But we struggle to find the words for it anyway. Or the images. I find all this is even more interesting the more digital things become, the more photography stands in for the body and the more the body becomes photographic. Sadly, there hasn’t really been a lot of updated discourse in the past decade about photography and these new relations, how it affects the way we think, or how it’s changed how we make art, music, food.

Being a victim is about having a physical experience that’s irreconcilable with language. You lose subjectivity, and for a moment, you are framed by an event. But we struggle to find the words for it anyway. Or the images.

Being a victim is about having a physical experience that’s irreconcilable with language. You lose subjectivity, and for a moment, you are framed by an event. But we struggle to find the words for it anyway. Or the images.

What’s the role of the readymade in all of that? Your photography is very concerned with material objects and begins by almost imbuing those objects with consciousness or emotions.

I’m attracted to photogenic things — there can be a lot of reasons for that, but usually it begins with the sense that the material I’m looking at will react well to being lit and framed. A viewer might not know what it is in the final image, but the important thing is that it’s not being caught or exposed, but rather kind of performing for the camera. My films make this scenario more obvious. All of the human subjects in my films already want to be photographed in so far as the characters are all performers: the first film is about a singer who sings a cover of The Sound of Silence; the second is about a teen dance crew making K-pop dance covers in Warsaw; and the third is set in China and follows the journey of an actress. So all these characters are photogenic and presenting themselves as images, and that subtext is the readymade element.

So you have a singer, a dancer, and an actor?

Yes, you could say it’s a bit of a triple-threat trilogy. I’ve always been interested in that trio of figures. Acting to me is about pure emotion, dancing is pure body, and singing is pure voice. Because they hold the capacity to transmit something much larger than an individual self, there’s this tension between being aspirational and being in some kind of trance state.

Which gets at this idea of the threshold — the threshold between the interior and the exterior, the animate and the inanimate. An interrogation of binaries, which seems to be present throughout your work.

I get very excited about new meanings that arise from strong contrasts. How different things placed close together are forced to interpret one another. It’s not about pretending binaries don’t exist or that we haven’t been totally formed by them — it comes more from a desire to reveal the nuances of codependency. I would say that codependency — in all of its toxic and affirmative forms — is an important idea to me. One thing is so often denied in order to absolve another thing. This especially extends to political regimes and how they might produce different types of images to reveal or conceal.

Your most recent film, ‘In Her Time,’ deals quite explicitly with how the government in China dictates the production of images. The protagonist, Iris, is an actress who has been hired to play the lead role in a historical epic film. But the subject matter of that film-within-the-film is never explicitly identified and is only hinted at briefly when Iris reads a book about the Nanjing Massacre. So there’s a layer of distance, but an audience member who is familiar with depictions of the Nanjing Massacre in Chinese culture would have certain images in mind once this is revealed, no?

Yes, I anticipated a Chinese audience and a shared understanding of what was being insinuated. I began the project thinking about revisionist history-making. In the US, it’s about reclaiming and revising histories to include people who have been overlooked. But in China, it’s about re-writing populism to uphold the authority of the government. Both ideologies use traumatic events as mythologies. The Nanjing Massacre has always been a strong platform for fostering anti-Japanese sentiment and marks a turning point in China’s independence. Its use in Chinese culture is quite similar to how the Holocaust is the central trauma for so much of Western story-making, from every Marvel movie to Harry Potter.

Is there a certain homogeneity to the images that this myth-making produces?

Definitely. Films on this topic are some of the most popular in China and so much of the imagery focuses on acts of violence against women. It is always depicted as this brutal sexual assault by the Japanese army against Chinese women — and women are extremely victimized in these depictions. All these movies use women being assaulted by the enemy as this symbolic mechanism, it’s the foundation upon which the nation can then take a moral position and move forward with purity. Reenactment as a potentially liberating act relates to the pleasure of violence, which is something people don’t want to admit.

The way that you handle violence in the film is very carefully done — it feels more like a repressed traumatic event than an explicit depiction. You use recurring imagery like mangosteens being crushed, for instance, or rifles poking through beaded curtains to intimate violence. Was it important to you, in your approach to putting violence on screen, to resist the literal reenactment of the event?

I didn’t feel the need to fully recreate certain things as I’m not particularly interested in the actual act of violence. I’m more interested in the invisible — in violence that is transmitted, hidden, condensed into a symbol, or even transmuted into something very beautiful. For example, in the film, there’s a scene that is basically set in a torture room and I would say that a metaphorical rape occurs through the use of objects, lights, and the rhythm of a repeated movement. But while this reading would be available to a Chinese audience because they know the brutality of the Nanjing Massacre all too well, it might not be picked up on by a Western audience. While it’s okay for there to be different interpretations, when I knew I would show the film in New York, I began to grow paranoid about it being consumed only as something ‘foreign’ or a story about something happening far away. So that’s when I re-edited the whole thing and created ‘Iris’ Version’ — in which Iris reflects on the whole experience of being filmed by me and is aware of the film’s circulation to the West. She takes ownership and mediates the possibility of being misunderstood.

I’m more interested in the invisible — in violence that is transmitted, hidden, condensed into a symbol, or even transmuted into something very beautiful.

I’m more interested in the invisible — in violence that is transmitted, hidden, condensed into a symbol, or even transmuted into something very beautiful.

Iris is shown behind the scenes, rehearsing lines and deliberating over the demands the film places upon her to master performing pain. And the second version introduces this other layer of mediation, with iPhone footage of Iris reflecting on the filmmaking process from an actor’s perspective. It’s almost a meta-version, questioning the idea of the performance we’re watching.

Yes, the new footage is her giving something like a meta-commentary across the whole film.

Meta-narratives interpolate the viewer — making us aware of our position watching a staged production. The way that you physically present your films does something similar. You build staged sets around the videos themselves, which create a sense of intimacy and are very different from the typical situation of a cinema.

I find that to preserve a sense of intimacy it is important to not obscure the staging. Every time I show my films, I want to make the viewer aware that they are stepping into a presentation and are choosing to be an audience to some kind of spectacle. It resists the idea of an immersive experience. The staging is never a set taken directly from the film, but more like how the film would like to be presented if it could live out its aims. The staging at the Whitney feels super intimate, for example, because there’s a giant bed in the middle of the room where the video is playing.

And, to go back to the question of “Iris’s Version” with its additional meta-commentary, was drawing attention to a secondary layer of artifice important to you for the same reasons? Is it about intimacy?

Well, I was trying to address Iris’s awareness of how images operate. She’s cast into this national imaginary but, at the same time, she also feels powerful acting in a role that allows her to be seen, even if the emotions and language she uses are not her own. But I think all the layers of awareness here feel weirdly organic to me. It’s just like with any piece of media — there’s the thing itself, but then there are the spinoffs and covers it spawns, or commentary, re-edits, memes. So it’s meta in one sense, but it’s also realistic in terms of how images and stories are circulated today, as well as true to the fact that Iris would have all those layers of awareness at once.

It’s also riffing on Neorealist conventions, in a way.

I’m definitely interested in Italian Neorealism as a kind of anti-Fascist filmmaking, where the subjects of films are ordinary people conveying their daily lives. French New Wave and its desire to communicate ethics or politics through formal decisions inspires me also.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs wrote this wonderful book, Dub, which takes its name from the ‘W’ of Sylvia Wynter — and Gumbs talks about Wynter as a toolbox. The idea of a toolbox is related to sources of inspiration of course, but somewhat different — and I wonder what you might say your toolboxes are?

Social media is a big toolbox for me. I’m interested in the inclusion of new media within a cinematic experience, and how it can be pushed towards a more formal realm — not in the sense of showing a text box or digital effect or whatever, but in a much more semiotic way. I mean it in terms of how social media has shaped time-space and how we bond with and idolize and consume one another, objects, sounds, etcetera. I like paying attention to all those little movements and their emotional arcs. In terms of toolboxes drawn from other films, I’m less sure… There’s something I find cheesy about a lot of contemporary cinema, especially in the production value, which is very homogenous. I prefer films made in the early aughts or 90s or earlier. Nowadays there’s so much that’s taken for granted, and indie just means a retro aesthetic and good, redemptive politics. There’s such a commitment to fictional realism within the form of what’s considered ‘cinema’ and that feels quite anachronistic. Everyone loved Anatomy of a Fall and Poor Things, for example, but they felt to me like they were made squarely in line with some preconceived notion of what a serious or epic movie should be. The last film I watched was A Heart In Winter by Claude Sautet. I’d seen it before, but I needed to see it again to remember why it moved me so much.

The film about the violin restorer? I saw it in the 90s I think.

Yeah, it’s kind of obscure but it’s about a very asymmetrical romance, about the possibility of not being able to love someone back, or not being able to empathize. Films have the capacity, as a long-form, to show this kind of unevenness. I think I’ve been very stuck on this as the thing that defines cinema for me.

Towards the end of In Her Time, Iris says, ‘If I hadn’t created my own world, I would have died in someone else’s.’ Can you explain that great sentence?

That line gets at the idea that Iris, as an actress, needs her own fantasy in order to not be totally crushed by the fantasy that’s been set up for her. But when I was writing that statement, I was thinking about how China is almost like an actress too, in that there’s this authoritarian script that needs to be played out and what individual agency could mean within those limits, but also in terms of how the West perceives China. There’s this constant questioning of whether we can trust China, what’s authentic and what’s not. We see China as an actress and we enjoy the melodrama of her performance. So, ‘If I hadn’t created my own world, I would have died in someone else’s,’ is also China’s statement to itself, justifying why its own self-isolation, world-building, and myth-making is necessary.

China is almost like an actress too, in that there’s this authoritarian script that needs to be played out and what individual agency could mean within those limits, but also in terms of how the West perceives China. There’s this constant questioning of whether we can trust China, what’s authentic and what’s not.

China is almost like an actress too, in that there’s this authoritarian script that needs to be played out and what individual agency could mean within those limits, but also in terms of how the West perceives China. There’s this constant questioning of whether we can trust China, what’s authentic and what’s not.

That’s very interesting. I had been thinking about world-building in a different sense with that line, especially given your interest in multimedia and new media — as world-building is of course often used in the context of video games. Have you ever thought of doing a video game?

I used to play video games with my brother a lot, but, if anything, I’d be more interested in writing fanfiction. Fanfiction is similar to video games in so far as it looks at a canon or a main narrative and extrapolates a tiny detail from that, which then inflects and refracts to form an entirely different world and outcome. Video games can be a bit teleological or strategy-based, while fan fiction is more horizontal, somehow. One choice spawns all these others — it’s actually kind of diasporic in terms of that narrative spread. I’ve been thinking about it a lot. I mean maybe I’m already making fanfiction.

It makes me think of another medium that is so central to your work: music. Music is also a space of role-play and fantasy.

For Tyrant Star and IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS, I worked on significant portions of the music before even beginning to film. The ideal scenario is that sound and image can co-develop, but not necessarily be in service of one another. I’m very conscious of not subjugating sound and music to the image. Music extracts sound from noise, and that kind of individuation, that kind of focus, feels related to photography to me. Even thinking about diegetic versus non-diegetic sound in my filmmaking allows me to play with the natural and the synthetic in a way that feels analogous to the photographic thinking space. I actually have synesthesia with the two: when I listen to music, I see images, and when I see images, I can hear music.

Dan Graham always said that we can only understand an artist if we also know what music they are listening to. What are you listening to at the moment?

I’m a human trash can, I listen to everything. I like the new. When I hear a pop song I like I immediately search for remixes, covers, choreography. Lately, I’ve been listening to this singer, NIKI, who once opened for Taylor Swift in Indonesia. She’s signed to an American label now and I love how she can sing about Los Angeles and Jakarta, weaving words like ‘Asian Calvinism’ and ‘Marxist’ into her Gen-Z heartbreak narrative. She’s a part of my current interest in Gen-Z nostalgia-core, which is a return to the acoustic, indie music of the 2010s. Bands are back again. I mean people are definitely still making music on the computer, but the post-internet consciousness of millennial PC Music is being usurped by the sincerity of acoustic affects. That was a big impetus for In Her Time, in the music itself but also conceptually.

Now that your trilogy of films is accomplished, what are you working on next?

I’m in the pre-production phase of a film about teen suicide in Northern California. It will be my first American film — I’ve actually only ever made films under post-Soviet or communist regimes, and never in English.

Do you already have the script?

I don’t usually work with scripts, but I have a treatment written for it because it’s more narrative. It’s about four girls who mimic each other’s suicides — based on an actual epidemic in Northern California where young people, often Asian, are ending their own lives because they’re not doing well enough in school. So it’s about performance once again, but mainly the performance of achievement and how that relates to individual subjectivity. I’m also examining a cultural clash, and positing the possibility that there might be truly different ontological premises between the East and the West. The philosopher Byung-Chul Han has been a big influence on my thinking around this.

Is there a book by Byung-Chul Han that you’ve been looking at in particular?

I love all his writing around burnout society and achievement, but I’m thinking specifically here about The Agony of Eros — which says that true love for an Other necessarily requires self-negation. He says that love is about being able to hold the other person’s difference, rather than consuming or eradicating it. Which makes him kind of anti-assimilation in a way that is useful for critiquing the American project.

I have all his books and am very inspired by his writing on rituals. We actually spent some time in Berlin together. In fact, the last time I saw him, he brought me a bottle of wine and told me that I needed to take it home, but that it absolutely could not break because that would be terrible luck. And the label said, ‘Lachryma Christi del Vesuvio:’ ‘tears of Christ from Mt. Vesuvius.’ I panicked a little because there I was at the Berlin airport with this bottle of the tears of Christ — and I realized I would have to check it in, but had no bag for it, so then I had to find some protective material to wrap it in, etcetera etcetera. Anyway, it survived the journey luckily and I’ve kept it ever since as a kind of fetish.

That’s really beautiful.

I wanted to ask you a question I like to include in all my interviews, which is about unrealized projects. We know so much about the unrealized projects of architects, which are often published, but so little about those of artists. There can be many reasons why a project is unrealized — whether it’s too big, too small, too expensive, too time intensive, or perhaps was self-censored — and I was wondering if you have any unrealized projects?

One unrealized project of mine is to start a talent agency in Vietnam — although maybe that’s more of a fantasy. I love to take materials and sculpt them and create perfect images. I like thinking through self-construction. My love language is attention and observation — helping people by offering them my vision and critique, kind of like teaching or therapy, but more hands-on. So it would be amazing to open a talent agency in Southeast Asia, find artists, and help produce albums, films, shows, etcetera.

I love to take materials and sculpt them and create perfect images. I like thinking through self-construction.

I love to take materials and sculpt them and create perfect images. I like thinking through self-construction.

Do you have any unrealized films?

I wanted to make a Vietnam War film about the banality of evil, not unlike Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, but more femme and maybe even less explicit. And then of course there’s this teen suicide film I’m working on, which is not yet realized and increasingly ambitious. I want it to have a Gen X ethos in terms of dealing with achievement and struggle — which has been inherited from post-war immigrant parents — but the aesthetic and casting will be in dialogue with a more globally networked Gen Z aesthetic.

I do research on millennials all the time as part of my work, but I haven’t yet done much research on Gen Z. So I’m very curious to hear how you would characterize that group and their aesthetics.

The most puzzling thing about Gen Z to me is their lack of a shadow side. There’s something weirdly un-shadowed about everything that they do. They seem to not care about freedom, but maybe no one does anymore. Whereas, when I was young, I was obsessed with ‘being free.’ Gen Z want to be good people but they only feel the right to talk about their own personal experiences. This is something I’ve noticed with art students of mine in group critiques in particular — no one feels permission to respond negatively to another student’s work or speak on their behalf. They also do a lot of digitization of the analog — they’re actually the ones reaching back into the analog archive of culture, digitizing it, and creating a new language around these things that millennials grew up on. I’m very interested in their nostalgia.

Are they particularly nostalgic for the 1990s and early 2000s?

I think it’s just a general melancholy that permeates. They’re nostalgic, but they don’t even know what they’re nostalgic for. They’ve been born into this moment in culture, in which we are, in both problematic and emancipatory ways, looking into the past constantly and exhausting history. The infinite ability to reach into the archive and repurpose it with a desire to make ourselves feel better has an effect on the contemporary consciousness. There’s something dangerous about always going into the past and applying whatever revisionist narrative we want to it. It’s the millennials who are making that revisionist content, but Gen Z is vastly affected by it, I think.

Well, on that point, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote this beautiful book of advice, Letters to a Young Poet. What would your advice to a young art student be in 2024?

Young people seem to need to externalize everything all the time, and it really takes away the basic tension of making art. I always tell my students not to post work in progress on social media, to keep secrets and not compulsively express, because the things that you may be wrong about or can’t communicate are so, so fruitful. One piece of advice, which is more particular to video art, is to question the very process of production. Young people are so apt to follow a commercial delineation of authority — they make a short video and then suddenly brand themselves ‘Directors of Photography.’ But the most important thing about video art is undoing that structure.

Art is not a solution to anything.

Art is not a solution to anything.

Speaking of younger generations and undoing systems of authority makes me wonder who you see as your peers. Are you part of an artist collective or a group of friends that you exchange work with, for example?

I’m not good at identifying with groups honestly, but if I were to really think about it, there are maybe three groups of people that all reflect a different part of me. One is about a shared cultural history, or a strong integration of the global. I feel like I probably know every Asian American/diaspora artist. There’s a real intimacy there of course, because of how provincial and Western-oriented the art world can feel sometimes. The second group is more like millennial artists I’m formally or professionally entangled with because of institutions, like museums and school. There’s actually more of a formal exchange of ideas here, and also a bond based on shared logistics, but I always feel very messy in relation to this group. Then I have friends who are younger — Gen Z or Gen Z-cusp — and don’t want to be artists or think art is radical at all. They’re more interested in writing, or music, or plays, things that are unsellable essentially. This lack of interest in professionalization is very inspiring to me, even if their politics can feel a bit too reactionary or cult-of-the-self. I feel that, as a millennial artist, it’s about navigating this split between institutional, good politics, and very informal, bad politics. And that spectrum feels so stratified at this moment.

We began this interview by discussing your photographic work and I’d like to bring us back there. Are you still working with photography?

I would say that photography is the smallest unit of all my thinking. It’s my mythology. My recent desire to respond to ‘the now’ has actually led me to a more analog place, process-wise. I’m curious about all the nostalgia, and what it’s for. So I’m actually making cyanotypes in the studio at the moment while trying to retain a digital consciousness. I’ll have to keep going for a while before I understand what’s happening there. Maybe it’s vain but I feel like I have to keep carrying on the burden of photography, or no one else will do it!

That leads to my very last question. Gerhard Richter says that, for him, art is the highest form of hope. What is art for you?

Art for me is often about what it isn’t. It shouldn’t be an attempt to reconcile things based on the same kind of symbolic regime that created the problem in the first place. We shouldn’t confuse freedom with power. Art is also the confidence to exist on your own timescale, as it can’t always be understood at the time that it’s made. Art necessarily has to exist outside of time and also outside of language, even if it’s made with language… Art is not a solution to anything. That’s the slogan answer!

AA:

what does the revolution will be televised mean to you

Chat GPT:

The phrase “the revolution will be televised” originated from a 1970 song by Gil Scott-Heron. It suggests that the struggles for change, especially political or social revolution, would be broadcast on television—though not in the way activists or revolutionaries might hope. Instead of being directly engaged in or informed by the grassroots movements, the media would likely sensationalize or commercialize the event. It captures a tension between the authenticity of grassroots struggle and the way it might be mediated or controlled by mainstream media.

To me, the phrase also speaks to the idea of spectacle in activism—how movements might be commodified or reduced to entertainment or soundbites when presented through media. It’s a reflection on how technology can both connect people and distort the realities of social change.

AA:

no, gil scott heron said the revolution will not be televised

Chat GPT:

You’re absolutely right—Gil Scott-Heron’s poem/song “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” actually emphasizes that real, transformative social change won’t be captured or sanitized by the media. It warns against the idea that media coverage will authentically represent or convey the true nature of a revolution or movement. The revolution, in Scott-Heron’s view, will be a grassroots, lived experience, not a spectacle for consumption or commodification on TV.

The phrase “The revolution will be televised” is often used ironically, referencing the disconnect between the real struggles of revolution and the way they are typically portrayed by mass media, which can dilute or distort their meaning. So, when people say “the revolution will be televised,” they may be acknowledging that, while media will likely cover it, it will never truly capture the raw, genuine heart of a revolutionary movement.

It’s a critique of the media’s role in shaping narratives and a reminder that meaningful change happens beyond the reach of spectacle.

AA:

so what would the revolution WILL be televised mean to you

Chat GPT:

“The revolution WILL be televised” flips the original idea on its head. If we take it literally and in a contemporary sense, it could suggest that social movements or revolutions are now not only covered by media, but actually shaped and influenced by the media itself. In the age of social media, live streaming, and 24/7 news cycles, revolutions and activism are happening in real-time, and the narrative is often driven by the visibility they gain on platforms like Twitter, Instagram, or TikTok.

In this sense, the revolution could be televised (or streamed, or shared) in a way that amplifies voices and causes, helping them to spread globally. However, there’s still the question of whether such media coverage is accurate or authentic. It might be more about spectacle or performative activism than genuine, transformative change.

So, to me, “The revolution WILL be televised” could mean that while media and technology can give revolutions unprecedented exposure, it also raises questions about the impact of that exposure. Is the revolution being commodified? Is it truly transformative, or is it just another trend being broadcast for consumption?