Pigeon House

In conversation with Sasha McEvoy

Photography by Devon Corman

Pigeon House

In conversation with Sasha McEvoy

Photography by Devon Corman

For Pat McCarthy, art-making goes clear past the creation of objects to be presented in a room. Being propelled by a sense of spirit in situ, of person among world and time, there is a consciousness to his work that is both present and storied, creating a universe that is filled with poetics, adventure, and romance, while being grounded in research that is local and agrarian. At times, his work is bizarre, anti-capitalist, and ritualistic, while also excitingly social and relational. He’s at once a pigeon flyer, a prolific zine-maker, a traveler, a poet, a punk, and now: a freaky wine connoisseur. His latest works are porcelain amphorae filled with the wines he harvested and cellared on his farm in the Catskill Mountains. The jugs are decorated with images of the flowers his wife grew this year, the mushrooms they foraged, the pigeons they raised, and, in one instance, an erotic collection of images from the artist’s self-published serial zine, American Cream.

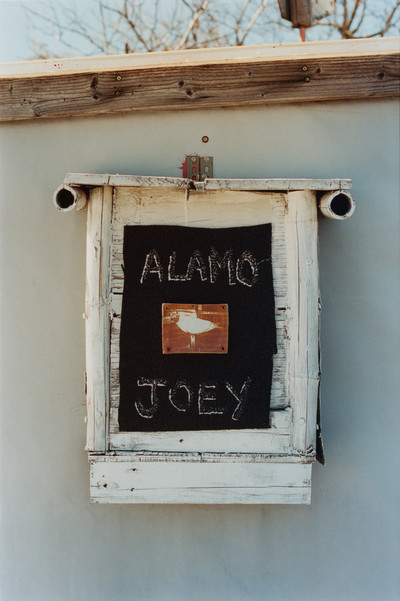

Pigeoning is this great tradition — everyone knows if there’s a pigeon guy on the block and everyone watches their birds spin around because they fly beautifully. The way they fly is specific to New York. It’s mesmerizing — like ballet or synchronized swimming. In order to pursue it, I had to get really into building architecture, and learn about managing life, like food and waste management systems, plumbing, and how you get water to a roof, all on a budget.

That sense of common architecture that lends itself to community and art really shows up in the performance aspect of your work. I’m thinking of your hot dog cart at Entrance gallery or the sandwich-making bike that you took across the ocean on a cargo ship.

Because I didn’t go to a traditional art school, I kind of fell backward into sculpture. I always had to lean into function. The things I make have to serve a function — or have motion — whether that means the thing has an engine or is alive, or that it functions in so far as it tells a good story with a beginning, middle, and end.

It’s the difference between an object of contemplation and a vestige of experience.

I always lean towards a vestige of experience: I did this thing in my life that was caused by X, Y, and Z and resulted in A, B, or C.

There’s something you said to me once that I think about often: that “the spirit of experience” is the source of all your work. Now, when I see that an artist has an idea, I want to know what their reasoning is for making it into an “art object.”

From the ages of eighteen to twenty-one —instead of going to college — I worked in the studio of the sculptor Tom Sachs. Tom famously makes functional sculptures, but he would quote Muhammad Ali: “It ain’t bragging, if you can back it up.” I took that to heart. I consider it with anything I’m making — I have to be able to “back it up” and have an honest connection with the object that I’m getting people to engage with. I want to respect their time and attention, especially as I’ve chosen an art practice that allows me to take my hobbies and launder them into the work.

From the ages of eighteen to twenty-one —instead of going to college — I worked in the studio of the sculptor Tom Sachs. Tom famously makes functional sculptures, but he would quote Muhammad Ali: “It ain’t bragging, if you can back it up.” I took that to heart.

From the ages of eighteen to twenty-one —instead of going to college — I worked in the studio of the sculptor Tom Sachs. Tom famously makes functional sculptures, but he would quote Muhammad Ali: “It ain’t bragging, if you can back it up.” I took that to heart.

How did that form of art-making start for you?

It started with zine making. In my teens to early twenties, I just tramped for years. I was really into hitchhiking and taking buses. I would save up three hundred bucks to fly to Europe and crash outside for a few months. I started making zines as a way to capture being a fuck-up transient and synthesize it into a finished product, into an artwork. I think that’s where I first started laundering my hobbies into a practice. So I went from travel to pigeons, to serving street food, and now to farming.

And this is happening on bigger and bigger “stages” as you continue.

Yeah, and I strive, especially now that I’m in my thirties, to have a practice that can bring everyone into the experience. Making art can be a really personal and isolating endeavor, but when it comes time for the exhibition, I try as hard as I can to bring everyone in. That’s why I always prioritize serving food, some bizarre food that I craft myself. The specific dish helps weave together the concepts and themes present in the show.

You also offer this strange kind of meta-narrative, especially when you’re in New York. You offer people a fresh way to engage with New York culture — but not with the sense of re-enactment.

I’ve always had a lot of friends who are musicians and something I really admire about their art form is audience retention. When you go see a concert, everyone’s in it, everyone’s listening, focused on the art, connected to the artists, and dancing. But when you go to a sculpture show, you walk through, look at the stuff, and five minutes later you’re outside talking to your friends about something else entirely. You’re quickly out of the experience. I try to have a lot of fun when I’m making art — I want that to extend to the show and not just be something I do in private.

And even thinking about when we were getting ready for the L.A. art fair, Felix, you were like “I’ve got this great idea to make a bunch of machines, iconic machines from iconic films.”

Yeah, “Iconic Vehicles from Icon Films,” like the snowcat from the end of “The Shining.”

And it’s not just that your work is site-specific, it’s also culturally specific: famous Hollywood movie machines in L.A.

And in the famous Roosevelt Hotel on Hollywood Boulevard!

It was amazing to see the sheer excitement of people trying to guess which machine was from which movie. It’s not a complex kind of participation, it’s an immediate feeling of being a part of it and also being fascinated by the object. People were immersed, like in a good film.

Nowadays I spend a lot of my time farming in the Catskills and part of being a farmer is becoming a gear-head. I have tractors and all of these funny vehicles, and that’s my day-to-day experience. So I want to talk to people about tractors and trucks, but that’s a hard conversation to have with all of my city people. So for that show in L.A., I decided to leverage cinema, which is maybe the single strongest driver in contemporary society of our collective imaginations. Maybe people haven’t ridden a John Deere lawnmower, but everyone — or everyone who has good taste in film — has seen “The Straight Story,” David Lynch’s masterpiece about an old, ailing farmer riding his John Deere across Iowa. So in sculpting those things, I was able to pull from my lived experience but tap into a broader collective imagination. I love things that live in our collective imagination — funny vehicles or pigeons, or growing flowers — there are thousands of years of human experience in raising flowers, which I think is even more special. I’m trying to make more art that participates in timeless hobbies.

Maybe people haven’t ridden a John Deere lawnmower, but everyone — or everyone who has good taste in film — has seen “The Straight Story,” David Lynch’s masterpiece about an old, ailing farmer riding his John Deere across Iowa.

Maybe people haven’t ridden a John Deere lawnmower, but everyone — or everyone who has good taste in film — has seen “The Straight Story,” David Lynch’s masterpiece about an old, ailing farmer riding his John Deere across Iowa.

You’ve mentioned you’ve been doing a lot more farming lately. When did that start?

In 2018, my wife and I took over a little former goat farm in the Catskill Mountains. We couldn’t afford a house, so we bought a barn, and I slowly built an apartment inside it. My wife Maddy is a professional gardener at Brooklyn Botanic, she’s a superstar horticulturist. And now we’ve spent six years sticking our hands in the dirt every morning, building soil, and cultivating fields and a vineyard and orchards. Toiling in the dirt is the natural next phase of my ecologically focused art practice.

For the past couple of years, Lazar and I have been getting a garden going in our backyard. It really came from this deep urge to be outside, to check on the basil and tomatoes, and water the plants. That urge when it comes is so undeniable and hard to supplement with anything else.

Cultivating life is a deep and rewarding ritual.

As an aside, I’ve been trying to read this new book and I keep getting to this sentence where the contrarian narrator won’t let her family have a dog because she thinks it’s a form of slavery. She’s saying it in this “funny way,” but it infuriates me because what this person is betraying about themselves is that they are completely out of touch with the depth of experience in living with animals.

Yeah, that’s a little reductive to me. I think of my animal husbandry as more stewardship than ownership. But I will say that I am interested in that tension in the politics of “keeping” animals. I’ve raised thousands of pigeons on my roof. It’s a serious pursuit requiring responsibility and attention. A unique and special detail in raising and flying pigeons is that these animals are free. They only come back if they’re happy, otherwise, they’ll go a block over to another pigeon coop or go live with the park pigeons. The reason people raise pigeons is to watch them bob, weave, and arch around the sky. It’s beautiful. And that’s the takeaway. I give them food and water every day, and they give me acrobatic performance art. They are not livestock.

A unique and special detail in raising and flying pigeons is that these animals are free. They only come back if they’re happy, otherwise, they’ll go a block over to another pigeon coop or go live with the park pigeons.

A unique and special detail in raising and flying pigeons is that these animals are free. They only come back if they’re happy, otherwise, they’ll go a block over to another pigeon coop or go live with the park pigeons.

You’ve described pigeon-flying to me as “anarcho” before. And it’s true — the exchange is so different because there’s no true ownership or possession. It’s very anti-capitalist in its engagement and relationship with living things.

And we’re not taking their flesh or eggs or fur or whatever. I think it parallels farming flowers. I’m not necessarily growing them to consume them and eat them, it’s more about food for the spirit and contributing to local ecology.

A more poetic exchange. As you’re getting into farming, I’m sure you’re finding more and more of this.

Yeah, way more experiments in this. I totally got the wine bug. I’m captivated by the farming of grapes and the science of making wine in all of these different parts of the world. We’ve been planting hundreds of grape vines. As with pigeon-flying, there are countless localized styles dependent on terroir, or hyper-local manifestations of style and tradition. Brooklyn is full of people making wine in their apartment basements, largely using all these tweaker New York breeds of grapes.

I would love to try some tweaker wine.

I think for the next show that we have together at Entrance, I’ll be on the street outside the opening with a big barrel of my shitty high-acid red wine and be topping off people’s glasses with a long wine pipet.

That’s something about your process — from hotdogs to wine, you find the thread of the maker and reflect those choices throughout layers of culture.

I want to say one thing about why I think hot dogs are cool. It’s the same thing about pigeons and everything in New York. They make hot dogs all around the world. They make sausages almost everywhere, and each culture has its own version. But the most iconic sausage is a New York dirty-water dog from a stainless steel street cart. That’s the most famous sausage in the world, and it’s so shitty. It’s similar to pigeons. Pigeons are the New York mascot, even though the pigeons here are pretty scuzzy. Despite everywhere else in the world having pigeons, in New York, they’re a part of our culture. I love that type of New Yorker-ism. New York also has its own fucked-up wine culture with all these hybrid grape varieties. They’re crosses between European grape breeds and native New York grape breeds — think crossing Pinot Noir with Welch’s Concord to make grapes that can grow in the extreme cold. I love that New York has its own way of doing these things that are kind of classic. They’re international classics, and New York’s got its own style.

AA:

what does the revolution will be televised mean to you

Chat GPT:

The phrase “the revolution will be televised” originated from a 1970 song by Gil Scott-Heron. It suggests that the struggles for change, especially political or social revolution, would be broadcast on television—though not in the way activists or revolutionaries might hope. Instead of being directly engaged in or informed by the grassroots movements, the media would likely sensationalize or commercialize the event. It captures a tension between the authenticity of grassroots struggle and the way it might be mediated or controlled by mainstream media.

To me, the phrase also speaks to the idea of spectacle in activism—how movements might be commodified or reduced to entertainment or soundbites when presented through media. It’s a reflection on how technology can both connect people and distort the realities of social change.

AA:

no, gil scott heron said the revolution will not be televised

Chat GPT:

You’re absolutely right—Gil Scott-Heron’s poem/song “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” actually emphasizes that real, transformative social change won’t be captured or sanitized by the media. It warns against the idea that media coverage will authentically represent or convey the true nature of a revolution or movement. The revolution, in Scott-Heron’s view, will be a grassroots, lived experience, not a spectacle for consumption or commodification on TV.

The phrase “The revolution will be televised” is often used ironically, referencing the disconnect between the real struggles of revolution and the way they are typically portrayed by mass media, which can dilute or distort their meaning. So, when people say “the revolution will be televised,” they may be acknowledging that, while media will likely cover it, it will never truly capture the raw, genuine heart of a revolutionary movement.

It’s a critique of the media’s role in shaping narratives and a reminder that meaningful change happens beyond the reach of spectacle.

AA:

so what would the revolution WILL be televised mean to you

Chat GPT:

“The revolution WILL be televised” flips the original idea on its head. If we take it literally and in a contemporary sense, it could suggest that social movements or revolutions are now not only covered by media, but actually shaped and influenced by the media itself. In the age of social media, live streaming, and 24/7 news cycles, revolutions and activism are happening in real-time, and the narrative is often driven by the visibility they gain on platforms like Twitter, Instagram, or TikTok.

In this sense, the revolution could be televised (or streamed, or shared) in a way that amplifies voices and causes, helping them to spread globally. However, there’s still the question of whether such media coverage is accurate or authentic. It might be more about spectacle or performative activism than genuine, transformative change.

So, to me, “The revolution WILL be televised” could mean that while media and technology can give revolutions unprecedented exposure, it also raises questions about the impact of that exposure. Is the revolution being commodified? Is it truly transformative, or is it just another trend being broadcast for consumption?